Determining the Attitudes of a Rural Community in Penang, Malaysia towards Mental Illness and Community-Based Psychiatric Care

J Ng, S Zaidun, S Hong, M Tahrin, J Au Yong, A Khan

Citation

J Ng, S Zaidun, S Hong, M Tahrin, J Au Yong, A Khan. Determining the Attitudes of a Rural Community in Penang, Malaysia towards Mental Illness and Community-Based Psychiatric Care. The Internet Journal of Third World Medicine. 2009 Volume 9 Number 1.

Abstract

Introduction

Attitudes toward mental illness have historically been that of stigmatisation and unfavourable responses (1). However, it was noted in a review article by Ng that attitudes among Asian populations have several distinctions as compared to those in the West. These differences arise because most psychiatric definitions originate in the West, which possess different cultural settings when compared with Asia (2).

Several prominent themes that exist among studies conducted in Asia about mental illness have a tendency to display somatisation as a way of dealing with an illness and a greater inclination to attribute mental illness to supernatural or religious phenomena. Conditions that are chronic, relapsing and irreversible are likely to carry a stigma and are judged to be stemming from supernatural or sorcery punishments, social transgressions or constitutional deficits (2). In most Asian societies, family members who are inflicted with mental illness are cared for by the family. While this may lead to a greater sense of shame and stigma, it may also offer potential support and care, which are valuable in the management of psychiatric illnesses.

Stigma also has implications for the patient himself, leading to increased psychiatric symptoms and stress, as well as reduced self-esteem. It also reduces the chances of a patient seeking treatment and leads to delays in recovery. Indeed, the stigma of mental illness may even be subjectively worse for the patient than the actual disease (3). Negative attitudes associated with mental illness go beyond mere stigmatisation, in a review by Romer in 2008, studies have shown that the mentally ill are frequently disadvantaged when it comes to matters such as access to housing, employment and health care (3).

A review of attitudes toward mental illness in various Asian cultures, conducted by Ng in 1997 also found that differences exist between different Asian ethnicities. In Malaysia, the Malay community was found to be more supportive and less rejecting towards the mentally ill. In more heavily urbanised Singapore, which is predominantly populated by ethnic Chinese, there was a prevailing unsympathetic attitude towards the mentally ill, resulting in many cases of suicide amongst sufferers. The Chinese attitude appears to be consistent with other East Asian cultures, such as the Japanese, who regard a mentally ill relative as a shame to the family (2).

There is a dearth of studies performed in Malaysia about attitudes toward the provision of mental healthcare through community facilities. Elsewhere in the world, a study conducted in London in 1995 showed that attitudes toward mental healthcare facilities have been shown to be surprisingly positive. It was found that most residents had no objections to the location of a community mental care facility within their neighbourhood (4).

The objective of this study was to determine the attitudes of a rural Malaysian community towards the mentally ill and to gauge their stance on the provision of community-based facilities for the treatment of the mentally ill.

Methods and Materials

Due to constraint of time a search on Ovid Medline for variations on the CAMI questionnaire found a study conducted in 2008 by Hogberg et al., which not only re-evaluated the relevance of the CAMI at that point in time, but also condensed the existing CAMI to a shortened version. In that study, they found that most of the items still retained their relevance despite the passage of time (6).

As much as possible, respondents were given the translated questionnaire to be read and filled in. If they had difficulties in doing this, the questions were read out verbatim to them and their responses solicited. Finally, the questions were paraphrased if they still had trouble understanding.

Results

Descriptive

i) Demographics

Out of the total 136 eligible villagers, 96 participated in this study giving a response rate of 70.6%. Those who did not participate were mainly because they were not contactable during the period of the study, unable to communicate effectively or because they refused to participate in the study. The respondents were mostly Malay (95.8%). There were 46 males (47.6%) and 50 females (52.1%), most were married (57.3%) followed by single (36.5%) and divorcee/separated/widowed (6.3%) while the highest level of education was up to secondary school (49%) followed by primary school (27.1%), illiterate (12.5%) and tertiary school (11.5%)

ii) Question Analysis

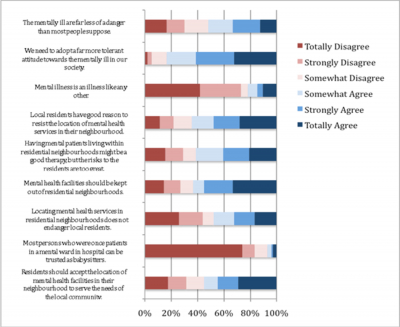

Figure 1 shows a stacked bar chart of the responses to questions in the Open-Minded and Pro-Integration strand. Most of the respondents (92.7%) felt that persons who were once patients in a mental ward could not be trusted as babysitters and most (78.1%) felt that mental illness is not like other illnesses.

Almost two-thirds of the respondents admitted feeling afraid about the thought of a mentally ill person living in residential neighbourhoods as shown in figure 2 which is a graphical illustration of the responses to questions in the Fear and Avoidance strand.

Figure 3 shows the responses to questions in the Community Mental Health Ideology strand. Most respondents tended to adopt a conciliatory attitude towards the integration of the mentally ill into mainstream society. About 78% of the respondents felt that the mentally ill should not be treated as outcasts of society and 82.3% agreed that no one had the right to exclude the mentally ill from the community. Support for community-based mental healthcare facilities was also strong (85.4%).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Discussion

The results of this study showed that attitudes towards mental illness in this community remain punctuated by fear to a certain extent. This could have probably arisen from a lack of understanding of the real nature of mental health. Research undertaken several decades ago in the USA has shown that the lay understanding of mental illness remained limited to florid conditions such as paranoid schizophrenia (7). A more recent systematic review by Angermeyer in 2007 from various studies in Europe and North America showed that most members of the public still did not have the ability to recognise various types of mental disorders (8). A more recent study undertaken in Malaysia by Yeap & Low has shown that knowledge of mental illness remains very poor in Malaysia, even amongst well-educated urban dwellers (9). Further compounding the situation in Malaysia is the fact that family members of the mentally ill are not spared from expressing a degree of stigma towards their mentally ill relatives (10). These findings remain broadly in line with the situation in Asia as a whole. Lauber’s review conducted in 2007, which assessed the situation of mental illness stigma among in the developing countries of Asia, showed that there was a general fear of the mentally ill in Hong Kong, as well as prevailing negative attitude towards the depressed in Turkey (11). As such, it would not be surprising to find that such negative attitudes arise due to a lack of knowledge and awareness of the various aspects of mental illness.

The level of stigma would also have implications for help-seeking behaviour amongst individuals who have concerns about their mental well-being. A Japanese study showed that individuals who had poor knowledge of mental disorders and possessing a higher degree of stigma were more likely to delay seeking treatment from the appropriate professionals, leading to potential deterioration due to the delay (12).

The respondents’ belief that former mentally-ill patients could not be trusted to be babysitters appears to stem from a perception that the mentally ill are unpredictable and dangerous. This appears to be in concordance with previous studies, which showed that most people still believed that the mentally ill are usually unpredictable, violent or dangerous (8,9). However, the understanding and tolerance displayed by the respondents toward the mentally ill in this study appeared to be in contrast with another Malaysian study (9), which found that most people wanted the mentally ill to be given less rights.

On the other hand, the response shown by the respondents towards the setting up of community mental health services to make the mentally ill as part of the normal community was very encouraging. This bodes well for the future development of mental healthcare services in Malaysia which intends to reduce the size of psychiatric institutions and becomes ever more geared toward general hospital-based and community-based care (13). In several Asian countries such as India and Thailand, steps have been taken with the assistance of the WHO to simultaneously reduce stigma while starting up community-based care facilities (14). These programmes have met with a degree of success and it does not appear to be impossible to replicate in Malaysia.

Conclusion

While stigma and fear of the mentally ill, especially among females, remain high amongst the study population, tolerance and acceptance of community mental health treatment appears to be strong. The effect of information, education and knowledge should be explored to see if the degree of stigma could be reduced.

Limitations

This was a comparatively small study with respondents who were mostly Malays. But the findings of the study should spur other researchers to conduct larger and detailed studies especially to know the responses among those who have family members or friends with mental illness, as a previous smaller scale study conducted in Sarawak, Malaysia has shown that this will affect the attitudes of respondents toward mental illness (15).