“Clinical Doctors as Qualitative Researchers”: QDAS Factors Informing Hospital Research Policy

P James

Citation

P James. “Clinical Doctors as Qualitative Researchers”: QDAS Factors Informing Hospital Research Policy. The Internet Journal of Medical Informatics. 2012 Volume 6 Number 2.

Abstract

Introduction

The role of Qualitative Data Analysis Software (QDAS) in qualitative research has become an imperative, as the application and use of qualitative research methods gain greater popularity (Fielding and Lee, 2002), whilst the

In many ways, QDAS packages are considered relatively fast in the processing ability of large amounts of data (media such as documents, video, photographs and audio) - Morse and Richards (2002). These can reflect the versatility in research approaches to working with data more interactively (Kearns, 2000) for deeper, contextualised investigation (Bassett, 2004), compared with the traditional qualitative analysis using manual card and paper techniques whilst leaving a visible and recoverable audit trail (St. John and Johnson, 2000) to support methodological rigour (Dey, 1993). As more and more researchers report using QDAS packages, their usage appears to have revolutionized the way research methodology and analytical work is carried out in qualitative research. However, the decision whether or not to use a QDAS package is based on the individual researcher’s requirements, as well as the researcher’s skills and experience with software and technology (Webb, 1999). Nevertheless, using such packages do not automatically create the methodological notion of qualitative analysis using the generated data, nor do they, by default, increase the robustness or rigour of the qualitative research method utilised. They can be considered a tool for the researcher to use. This raises the first research question,

What is Qualitative Data Analysis (QDA)?

Using the Constant Comparison Method of Analysis in QDAS Packages

The constant comparison analysis (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) is likely to be the most commonly contemplated type of methodological employment utilised in the analysis of qualitative data. This raises the term “coding” when referring to this type of analysis (Miles and Huberman, 1994) resulting from thick, rich descriptions that are seemingly situationalised and contextual in nature (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2004). This is often preceded by a 3-stage process of open, axial and selective coding that seeks to underpin the constant comparison method (Patton, 2002) by moving from an open-coding process to the constant comparison method which draws upon finely tuned theoretical and cyclic analytic researcher skill building and development (Ryan and Bernard, 2003). Utilising the constant comparison method is often undertaken deductively (codes are identified prior to any analysis (Miles and Huberman, 1994) and then looked for in the available data – an apriori process), but it can also be conducted through an inductive process (codes emerge out from the data), or abductively (codes emerge from the application of a continuing cyclic and iterative process) which adds another demonstration of validity for qualitative research outcomes. Using QDAS packages, this allows the researcher to code data directly and in real-time, splitting the data into more manageable and visible components and identifying or naming these segments by assigning themes and located sub-themes. The text data can also be coded and recoded dynamically (Strauss and Corbin, 1998) and easily into any new emergent concepts, categories, or identified themes and in some cases help develop appropriate models as the analysis progresses; the new coding categories can be compared (cross-referenced) with respect to other coded responses or tabled questions (Bazeley, 2006). The use of QDAS packages appears to speed up this research process and becomes more flexible as a result, as the software helps the researcher ask questions to

When choosing a QDAS package the researcher’s style of working with the available data is paramount and the package needs to be flexible enough to allow the researcher to interrogate the generated data and develop the required analysis in a natural way. It is the type of qualitative analysis associated with the requirements of the research questions that dictates which package is more suitable to use (Williams, Mason and Renold, 2004). Consequently, the choice of package can dictate the type of analysis to be performed and care needs to taken in the final choice of software package. In some circumstances more than one may be used (Mangabeira, Lee and Fielding, 2004), as the data analysis and subsequent literature engagement may force different approaches that lead to different software package treatments. In essence, for most researchers one package could be all that is needed. In other research circumstances, multi-package engagement would need to be utilised, as the specific and on-going research orientation demands different data treatments that can only be done through multi-package use. One very important and evident problem in using QDAS packages is how to display and model the patterns and relationships found in the data. Unfortunately, many researchers claim they have used these types of packages for the data analysis but fail to show specifically how their structural/theoretical propositions have been arrived at as a direct result of an engagement in the software and its corresponding analysis. This is mirrored to some extent by Glaser (2004) for example, who states that …

Methodology

To consider the application of QDAS issues involved in the support of research methodology closely, this empirical paper employed an interpretive approach. This used a semi-structured questionnaire utilising a focus group, as is now common practice for such enquiries (Krueger, 1994). This provides an appropriate element of context and flexibility (Cassell and Symon, 2004). Given the lack of purposeful research in the area of software use and qualitative methods in health in Thailand, this methodology is seen as appropriate for generating contextual data supporting the purpose of underpinning enriched theory development (Cayla and Eckhardt, 2007), and informing

The population for this study were all doctors who have conducted qualitative research as part of their professional development at a medical facility in a Thai private hospital in Bangkok, Thailand (derived from Carman, 1990; and Glaser, 2004) and the resultant sample frame was based on convenience sampling (after Harrel and Fors, 1995). The criteria of theoretical purpose and relevance (Glaser and Strauss, 1967) were applied to the identified population.

Consequently, all doctors were included in the population frame as individuals (material objects) that form the focus of the investigation (Bryman and Burgess, 1994) - resulting in 22 available research informants, who could speak English (second degree and trained overseas) and could account for their views in terms of the research orientation (Morse, 1994). The departments involved were – Clinical Pharmacology; Diabetes and Endocrinology; Anaesthesia; Cardiovascular Medicine; Immunology; and Infectious Diseases (Not all departments in the hospital were conducting research projects – those that did are included here). Each doctor was given a number and using a random number approach, a group of twelve (12) were chosen (Onwuegbuzie and Leech, 2005a; Carrese, Mullaney and Faden, 2002). Twelve (12) were chosen, as this was the number considered optimum in a focus group (Vaughn, Schumm, and Sinagub, 1996; Johnson and Christensen, 2004) in order to provide expected levels of interaction. This was considered an appropriate sample size for this qualitative research orientation, as it is driven by the need to uncover all the main variants on a research conception (Kember and Kwan, 2000). Levine and Zimmerman (1996) suggest that a further important consideration of using the focus group was that this method innately acknowledges

The focus group outcome was manually coded initially using Acrobat according to themes and sub-themes that 'surfaced' from the interview dialogue using a form of wide open-coding, which is derived from Glaser (1992a), and Straus and Corbin (1990) constructing first-stage analysis. This treatment was also reinforced through deep and surface approaches (Gerbic and Stacey, 2005) and extended through the use of thematic analysis conducted using the NVivo qualitative software package (Walsh, White, and Young, 2008) while using a mind-mapping sequencer to test connections and residual legacies. 392 specific codes were developed which in turn fitted into 9 main themes and 27 sub-themes. In this way, no portion of the focus group dialogue was left uncoded and the outcome represented the shared respondents views and perspectives through an evolving coding sequence (Buston, 1999). Various themes were detected and acknowledged whilst using the NVivo qualitative software package, as well as from the application of manual coding and utilising the constant comparative approach where new instances were constantly compared to the theme with those already encountered until this saturated the derived category. This triple form of interrogation was an attempt to increase the validity of the choice of both key themes and sub-themes through a triangulation process. NVivo was further used to explore these sub-themes by helping to pull together each of these sub-themes from all the interviews (Harwood & Garry, 2003). It was thus possible to capture the respondent's comments on each supported sub-theme and place them together for further consideration and analysis.

Presentation of Framework Outcomes

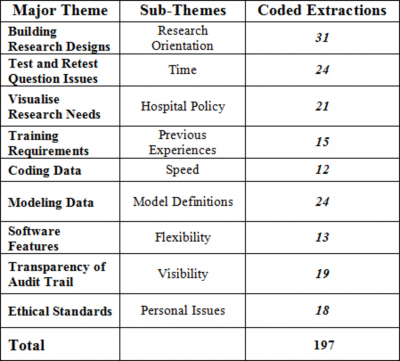

The research questions were mapped to the generated 9 major themes, and is supported by 27 sub-themes, as indicated in Table 1 - Major Themes, Research Informing Notions, and Informing Hospital Research Policy. The major themes are further discussed below. The outcomes of this research inquiry in terms of the 9 major themes and the total number of references for these themes are further indicated in Table 2. Figure 1 presents a model of the discussed main outcomes. These are further reduced to connect the major theme to a significant sub-theme where additional analysis was conducted, which revealed 4 key areas of outcomes (Figure 2).

Discussion

The style adopted for reporting and illustrating the data is partially influenced by Gonzalez, (2008); Carpenter, 2008; and Daniels et al. (2007) and is formulated below, focusing on the raised main themes. The subsequent sub-themes are presented in Table 2. The discussion format used in this paper reflects the respondents' voice in a streamlined and articulated approach using Table 2, below, also shows the breadth of coded respondent illustrations/extractions as used in the reporting of this research.

Figure 2

Building Research Designs

An approach by doctors was to use the software to build a research design as they went along. For example, one respondent (D5) suggested that ...

Test and Retest Question Issues

Since the questions have been underpinned from the literature using the research loop, there is still the need to test the derived data from respondents. In this respect, one respondent (D3) suggested that …

Visualise Research Needs

Visualising the research needs appeared to be a surprise factor, as the connection between research needs and research outcomes are often blurred. However, one respondent (D1) suggested …

Training Requirements

Most doctors appeared to believe that they were not experienced in qualitative research methods and needed some form of training. This aspect is supported by one respondent (D3) who stated emphatically …

Coding Data

Doctors who had used software for qualitative research tended to support the notion that software made research easier to analyse. As one respondent (D2) indicated …

Modeling Data

Modeling data is an art that is difficult for many researchers. This refers to the data contextualized through code and cemented together under a category or theme. As one respondent (D9) highlighted …

Software Features

It would appear that doctors find that the qualitative software takes too long to learn and does not really benefit the patient in terms of medical outcomes. As one respondent (D4) stated …

Transparency of audit trail

It was recognised by many respondents that the audit trail was an important aspect of qualitative rigour. As one respondent (D7) indicated …

Ethical Standards

Overall, ethical standards appeared to over-ride all research decisions. As one respondent (D8) stated …

The three research questions (above) therefore surround the application and implications of using software in qualitative research. This is modelled in Figure 1, below.

As can be seen from Figure 1, the doctor’s research views and research questions are mapped together to illustrate how mind-mapping software can show the linkages and respondent extractions. It is also noticeable from Figure 1 that the left side relates to the questions and software, and to the right it relates to the Doctors views about managing data and its interpretation whilst reflecting present hospital policies. Out of 392 coding extractions, Figure 1, underpins the major outcomes as - Q1 – 14; Q2 – 8; and Q3 – 7 which are considered appropriate and context sensitive.

What are implications for Hospital Research Policy?

Table 3 below, shows a summary of main, sub-themes and more useful coded extractions totaling 197. This does not mean that more extractions are more important, but in the context of a focus group, more time and greater consideration was given to these elements and therefore these are deemed to be of greater significance in terms of the outcomes for the respondents.

For developing hospital research policy therefore, this paper will now address each main theme in terms of the 4 elements (personal, administrative, research tools and research process) as contained in the following model:

Policy Implications for each highlighted area from Figure 2 are discussed below.

For example, when utilising a qualitative method to help visualise research needs, the process and outcomes may not necessarily be as expected in the quantitative orientation. Training, specifically more training in qualitative methods, may be an added burden for hospital research engagement, without the ability to offset the costs associated with this form of methodology. However, because of the bureaucratic culture of the hospital in general, and the need to follow quality management protocols, then the audit trail should be very transparent and this should help engineer greater acceptance of qualitative outcomes in a financially oriented culture whilst building-in research oriented best practices (Cooper, 1999).

Research training isn’t taken as seriously as it is expected, and those doctors engaging in research already have the tools and experience to conduct their research, as most research is non-mission critical (Kostoff, 1993c). However, for mission-critical clinical trials experiences and research methodology knowledge appears to provide confidence in managing these large capacity processes. However, it is probably the lack of appropriate doctor’s research experiences that reduces the hospitals capability to conduct more mainstream research –through treatment, supportive care or prevention trials (Shweta, Vidhi, and Satyaendra, 2007).

Possible Benefits of the Application of QDAS to Doctors Research

When mapping out the benefits of one QDAS package against the researchers data needs, the data always took precedence – corresponding to the methodological orientation. In this way, the QDAS package can be seen as an instrument that helps “doctors as qualitative researchers” analyse data streams more effectively (Welsh, 2002) and reduce data into more manageable segments through the processes of categorization and hierarchal relationship building (Atherton and Elsmore, 2007). Notably, it was understood from the data that the original format of the data available for analysis will often determine which QDAS package is more useful. Inevitably, compromises are often made and the data transformed and revised to adapt to each particular QDAS operating parameters – as each software package will ultimately provide a different generalised framework that “doctors as qualitative researchers” will need to learn and accommodate methodologically. The choice of QDAS package also depends on how the researcher expects to undertake the data analysis (Weitzman, 2000) as the qualitative researcher is the main tool for analysis, regardless of whether QDAS is employed in the data analysis (Denzin and Lincoln, 2005b) or elsewhere in the project. Consequently, a doctor’s approach is literally bound to treat the software package as a tool.

One of the first benefits is that using software speeds up analysis tasks considerably. This was recognised by many doctors; because utilising QDAS packages to search for important phrases, create text segments and code them, cross-reference memos to text and codes, create cross-references between parts of the text, can easily be carried out very efficiently and swiftly. This did not seem to compromise the feelings of keeping close to the data (contrary to Barry, 1998) as many qualitative researchers require - as the QDAS package does not carry out any kind of independent qualitative analysis. Over time and with appropriate experience, reliance on hand-built and manually adopted schemes of qualitative research analysis will retreat and more functional and flexible QDAS packages will appear to take their place.

Other major benefits of using QDAS are interactivity and collaboration (Asensio, 2000), which enhances avenues for flexibility throughout the research process (Lewins and Silver, 2007). This allows the researcher to focus on the meaning of the data streams through digital convergence (Brown, 2002) whilst providing adequate transparency through an audit trail (St. John and Johnson, 2000).

Possible Limitations Associated with the Use of QDAS

Consequently, there is nothing more unequal about the equal treatment of QDAS package applications to qualitative approaches. However, this appears to be more of an issue with novice or first-time qualitative researchers as they often lack a critical perspective (Mangabeira, Lee and Fielding, 2004) of the application of QDAS packages on qualitative processes and methodologies.

Further, it would appear too many doctors that some preliminary structuring of the research arena – based on the outcomes of a literature review - are often tenuous and signal inadequate research design as well as inadequate attention to the literature which leads to poorly structured analytic outcomes that are unsupported either by the literature or by the adopted analysis techniques. In this way “doctors as qualitative researchers” are drawn into thinking that their methodological process is robust and secure. To mitigate this, coding should be continuously reviewed and rechecked (Loxley, 2001) and planned and supported using mind-mapping techniques. QDAS applications appear to doctors to separate out the real data from the reporting where quotations from interviews are often used as a substitute for analysis (Gibbs, 2002) and used to impart a ‘

There was some disagreement on a theoretical level as to whether the use of QDAS packages may make qualitative data more quantitative in nature. However, Hwang (2008) indicated that this may be just attempting to make the research process more effective through transparency and enhancing reliability of the data analysis processes using visual and deductive elements of various QDAS packages. This outcome supports the notion of applying ethical standards and in utilising the transparency of the audit trail.

Other QDAS dilemmas that were raised by doctors include the pacing of data collection, the volume of data, the procedure and rigor of data analysis, the framing of the ensuing analysis and the software product (Glaser, 2001). However, the qualitative researcher should always remain in control of the data analysed and some QDAS packages provide more effective ways for this to happen. Fear, lack of knowledge, when to end, when to use other methods, ease of use of software, Cross-case thematic analysis, complexity of software, software availability and price, features and flexibility of software, triangulation, speed, presentation of result outcomes are depicted in different ways. Close attention to the effect of each QDAS package on similar data sets may help determine the efficacy of the rigourous of adopted qualitative research method.

Conclusion

The use of QDAS packages in qualitative research is gaining ground and for some “doctors as qualitative researchers” they offer speed and flexibility in assessing and analysing large volumes of generated data. QDAS packages are utilised by small numbers of qualitative researchers that attempt to use technology to explore and make sense of qualitative related data. However, this is about to change as QDAS packages like NVivo have now been developed to a point where their usefulness and inner technical abilities can enhance qualitative researchers primary investigation, methodological and data analysis response. The application of QDAS packages for “doctors as qualitative researchers” and their influences on hospital research policy have gone beyond just data analysis as long as doctors follow ethical guidelines in conducting research. This will also give greater support to clinical doctors engaging in qualitative evidence-based research leading to more effective primary care solutions.