The Prognostic Factors Of Tuberculous Meningitis

Z Ahmadinejad, V Ziaee, M Aghsaeifar, S Reiskarami

Keywords

hydrocephalous, iran, meningitis, prognosis, tuberculosis

Citation

Z Ahmadinejad, V Ziaee, M Aghsaeifar, S Reiskarami. The Prognostic Factors Of Tuberculous Meningitis. The Internet Journal of Infectious Diseases. 2002 Volume 3 Number 1.

Abstract

Introduction

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that one third of the world's population is infected with mycobacterium tuberculosis, with the highest prevalence of tuberculosis in Asia [1,2,3]. Tuberculous meningitis (TBM) is one of the most common clinical and morphological manifestations of extrapulmonary tuberculosis and remains a serious health threat in developing countries [4,5,6].

The risk of progression of the primary tuberculosis (TB) to TBM is higher in children than adults and the percentage of which is said to be 0.3% of untreated primary infection in children [7,8]. It may occur at any age, but the highest incidence is in the first 5 years of the life [9,10,11]. Tuberculous meningitis accounts for 20-45% of all types of tuberculosis among children, when compared with only 2.9-5.9% of adult tuberculosis [9,12].

However, despite of the advent of the newer antituberculosis drugs and modern imaging techniques, mortality and morbidity remains high [13]. Most studies has suggested that combination of various factors like delayed diagnosis and treatment, extremes of ages, associated chronic systemic diseases and advanced stage of disease at presentation may contribute to this high morbidity and mortality rate [6,7,14,15,16].

In this study, we evaluated certain clinical, laboratory, neuroimaging and therapeutic factors associated with mortality.

Patients and Methods

Over a period of 10 years (1992 to 2001), 96 patients with TBM were admitted in three major teaching hospitals in Tehran.

Diagnosis of TBM was based on the clinical, cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) and radiological images and pulmonary involvement [17]. The clinical criteria were: fever, headache, meningismus signs and other clinical presentations of meningitis lasted for more than 2 weeks. Furthermore, typical CSF features including pleocytosis with more than 20 cells, lymphocytes greater than 60%, protein greater than 100 mg % and glucose level less than 60% of the corresponding blood glucose level was necessary to confirm the TBM [17,18].

In this study, we simultaneously evaluated both presumptive and definitive TBM patients, as typically performed in other studies [6,19,20,21]. Presumptive diagnosis was based on clinical criteria with typical CSF features and at least one of the following supporting criteria was observed: 1) Isolation of mycobacterium tuberculosis from body secretion other than CSF in smear and/or culture, 2) Radio-graphic findings based on chest X-Ray that confirmed pulmonary TB (reticulonodular pattern in upper lobes with or without cavitary lesions), and 3) Hydrocephalous from brain computerized tomography (CT) scan. All presumptive TBM patients had negative culture for bacterial and fungal agents and negative Indian ink.

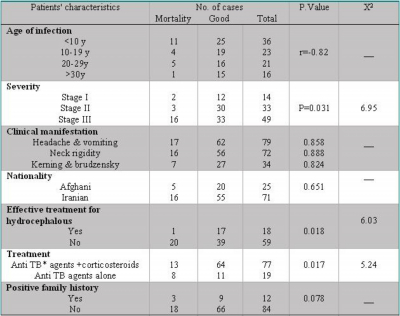

The severity of TBM at the time of admission was evaluated and categorized into three stages as shown in table 1[ ]. Brain CT scan studies were carried out on all patients at the time of admission (a follow up CT and/or magnetic resonance imaging was done in case of clinical deterioration). The findings of the initial CT scan have been analyzed.

Figure 1

Patients were given antituberculosis treatment consisting of four drugs including: isoniazid, rifampin, pyrazinamide and ethambutol. Other promising antituberculosis agents such as streptomycin, ciprofloxacin and amikacin were used temporarily in patients with drug toxicity.

Based on therapeutic outcome the patients were divided into two groups, i.e., poor outcome and good outcome. Therapeutic outcome was considered as poor outcome in deceased patient.

Variables including initial clinical manifestations and severity of TBM at the time of admission at the hospital, initial laboratory findings, age, sex and hydrocephalous and corticosteroid adjuvant therapy between the two groups (good outcome and poor outcome) were analyzed, using X 2 -test or Fisher's exact test.

Results

The patients included 46 (47.9%) males and 50 (52.1%) females. Forty-nine patients (51%) were lower than 15 years old (26 pt<5y) and 47 (49%) were more than 16 years old. The diagnosis of TBM was confirmed in 22 (22.9%) patients by the presence of Acid Fast bacilli in CSF smear or culture or PCR. On admission, 14 patients (14.6%) had stage I TBM, 33 (34.4%) stage II and 49 patients (51%) stage III. Of the 96 patients, one had acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) and one had agammaglobulinemia. Twenty-five patients (26%) were Afghani and 71 (74%) were Iranian.

Headache, vomiting and neck rigidity were the major clinical manifestations found. The clinical manifestations of the patients in this study are listed in table 2. Twelve patients were found with family history of tuberculosis. Twenty five patients (26%) had positive tuberculin skin test (indurations>10mm).

Figure 2

Cranial nerve palsy, including ophtalmoplegia (abducens palsy) as the most common cranial nerve palsy, was present in 25 patients (26%). Among 96 patients, 77 (80.2%) had hydrocephalous in their cranial CT scan, and of these, 18 (23.4%) underwent shunt surgery or medical treatment with furosemide. The CSF parameter findings are listed in table 3.

Figure 3

The treatment protocol, which is discussed in the patients and method section, was resumed in all patients. Corticosteroids were used in 77 patients (80.2%).

In this study, 21 patients (22%) died during admission. Of these 21 patients, 11 (52.4%) were less than 10 years old, 4 (19%) were between 10-20 years old and 1 was above 20 years old (r=-0.82). The potential prognostic factors for the two patients groups (good outcome vs. poor outcome) are listed in table 4.

Figure 4

*Antituberculous

Significant among these prognostic factors were the patient age (<10y) (r=-0.82), the severity of TBM at the time of admission (P=0.031), the effective treatment of hydrocephalous (P=0.018) and corticosteroid therapy (P=0.017).

Discussion

Tuberculous diseases are still relatively common in countries such as the Middle East and southern Asia where the disease is endemic[3]. Tuberculous meningitis is one of the major infectious causes of chronic meningitis worldwide (including Iran), with high mortality and morbidity [23,24].

The overall mortality rate in this study was 22% (21/96), a figure which is close to the lower limit of the reported mortality rate [14,15]. The significant prognostic variables derived by univariate analysis in our study included the staging of TBM at admission, the effective treatment of hydrocephalous, age (<10y) and corticosteroid therapy. Other studies regarding the prognosis of TBM, which employed univariate analysis, had revealed the important role of age, stage of TBM on admission, mental status and associated extra enhancing exudates on CT scan [14,25,26,27].

Stage of the TBM on admission indicates the severity of disease. The severity of TBM on admission was a significant prognostic factor with those in stage III having a 32.6% mortality rate, which was in accordance with other reports [5,6,19,25].

The age of the patients (especially <10y) was a significant prognostic factor in our study. Age has a different role on prognosis of patients with TBM in different studies. In some study, lower age was found to be a good prognostic factor [6,15,28]. However the significant association between low age, particularly lower than 5 years and grave prognosis was also noted in other studies [29,30,31]. However Chang et al [21] in their study have shown that age was not a significant prognostic factor. The differences between the results of various studies might be due to the age of the studied population.

In our study, neither the clinical manifestations nor the CSF laboratory findings were a significant prognostic factor. Although a low CSF glucose level [5] and high CSF protein concentration [5,21] has been found to be a significant prognostic factor.

Eighty percents (77/96) of our patients had hydrocephalous, where as in other studies, it was a wide range differing from 23% to 80% [15,32,33,34,35]. Frequency of hydrocephalus was found in children higher than adult [31,32,34,36]. Although some degrees of hydrocephalous is present in all patients with TBM [14,36], it was found that the prognosis is worse in patients with obstructive hydrocephalous when compared to those with communicating hydrocephalous [14]. It is a common but treatable complication of TBM, which significantly influenced the prognosis, and unlike other prognostic factors, its presence would change the management of the patients [5,18,19,20,21,35,37]. Timely surgical intervention in patients with hydrocephalous may have a critical role in the outcome [6]. The critical role regarding the management of hydrocephalous and prognostic outcome was documented among our population.

The routine use of steroids for treatment of TBM is still debated [37,38]. Some investigators believed that patients presenting with severe disease may benefit from steroid therapy [15,38,39,40,41,42]. Their value in reducing cerebral edema and inflammatory exudates and preventing spinal block, particularly in infants, appears to be generally accepted [39,43]. It is not at all clear that steroid therapy might have a prolonged beneficial clinical effect [21]. However, in our study, adjunctive corticosteroid therapy had a good role on the outcome.

In summary, TBM, a central nervous system infectious disease with high mortality rate, especially in children, is still a serious public health problem. The presence of hydrocephalous, severity of TBM on admission and the lack of adjunctive corticosteroid therapy are strongly associated with mortality rate. Some of the prognostic factors are correctable. Therefore, early diagnosis, early use of antituberculosis treatment, corticosteroid therapy and treatment of the associated complications such as hydrocephalous are mandatory.

Correspondence to

Zahra Ahmadinejad Department of Infectious Disease. Imam Khomini Hospital, Keshavarz Blvd, Tehran, Iran Telfax : + 98 21-6929216 Email : Ahmadiz@sina.tums.ac.ir