Development of a Prototype Questionnaire to Survey Public Attitudes Toward Stuttering: Principles and Methodologies in the First Prototype

K St. Louis, B Lubker, J Yaruss, T Adkins, J Pill

Keywords

attitudes, sampling, stereotypes, stigma, stuttering

Citation

K St. Louis, B Lubker, J Yaruss, T Adkins, J Pill. Development of a Prototype Questionnaire to Survey Public Attitudes Toward Stuttering: Principles and Methodologies in the First Prototype. The Internet Journal of Epidemiology. 2007 Volume 5 Number 2.

Abstract

The

This research project was carried out at the Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology at West Virginia University using resources of the Department.

Project Overview, Rationale, And Measurement Issues

Long-Range Goals

A task force was convened in 1999 to launch an international initiative devoted to exploring public attitudes toward stuttering. Its long-term objectives were to develop a survey instrument that could effectively obtain baseline measures of public attitudes toward stuttering in comparison to various other stigmatizing conditions potentially in any part of the world. Once completed, the empirical data to be gained from the instrument could be used by various stakeholders to foster and to evaluate effectiveness of strategies for mitigating societal stigma to which people who stutter are subjected. St. Louis (2005) briefly reported the rationale and vision for this “International Project on Attitudes Toward Human Attributes” (IPATHA). This paper elaborates the rationale and vision followed by explanations of initial steps in the development of an instrument designed to obtain such baseline measures. Specifically it describes the rationale, design, and initial field-testing of the first experimental version of the Public Opinion Survey of Human Attributes (POSHA-E).

Rationale

Scope of the Problem of Stigma

Stigma, regarded by Goffman (1963) as the manifestation of a “spoiled identity,” is a universal human experience. Individuals who are regarded as being undesirable or potentially dangerous often live with ridicule, bullying, and illegal discrimination. As a result they do not seek or receive the health care or specialized treatments they need and may experience lifelong negative consequences in education, employment, promotion, and social acceptance. Since Goffman's seminal work, stigma has been recognized as an important area of scientific inquiry. Stigma and its behavioral manifestation, discrimination, negatively affects health, both physically and mentally, of more than one billion of the world's population (Wahl, 1999; Weiss, Jadhav, Raguram, Vounatsou, & Littlewood, 2001). Moreover, stigma and discrimination are especially powerful in low- to moderate-income (developing) countries and marginalized groups in high-income (developed) nations (Ustun, Rehm, Chatterji, Saxena, Trotter, Room, Bickenbach, et al., 1999). If stigma could be reduced, the well-being and health of millions could be improved.

Available evidence clearly indicates that negative public attitudes can have dramatic negative impacts on the lives of people with a variety of stigmatizing characteristics. Mental illness is one area that has received perhaps the greatest attention (e.g., Crisp, Gelder, Rix, Meltzer, & Rowlands, 2000; Gelder, 2001, Sartorius, Jablonsky, Korton, Ernberg, Anker, Cooper, & Day, 1986; Thompson, 1999; Thompson, Stuart, Bland, Arbolele-Florez, Warner, & Dickson, 2002), but stigma affects people with numerous other conditions, including communication disorders. As noted above, this field study focuses on the specific communication disorder of stuttering.

In the case of stuttering, stigma is often discussed within the context of a “stuttering stereotype” (Blood, 1999; Cooper & Cooper, 1985; Ham, 1990; Reingold & Krishnan, 2002). Moreover, stigma has been shown to change or vary according to specific variables. For example, when stuttering persons are acquainted personally with respondents, reported stigma seems to disappear (Klassen, 2002). None of the foregoing means that physical aspects of many stigmatized conditions are unimportant in consideration of health outcomes. For stuttering it is well known that physiological and neurological differences exist between stuttering speakers and nonstuttering controls, when groups are compared in physiological domains such as genetics and brain function (e.g., Drayna, Kilshaw, & Kelly, 1999; De Nil, Kroll, Lafaille, & Houle, 2003). Nevertheless, social environments play an important role in the way stuttering is experienced, how it develops, and its effect on persons' lives (e.g., Conture, 2001; Smith & Kelly, 1997; Yaruss & Quesal, 2004).

Measuring Stigma

Increasingly, there are calls for public awareness and education campaigns to diminish stigma associated with stuttering and other conditions (e.g., Blood, 1999; ILAE/IBE/WHO Global Campaign Against Epilepsy, 2002, Klompas & Ross, 2004; Langevin, 1997; NAAFA, 2002; Wahl, 1999; WHO, 2001). The rationale is that if groups who are stigmatized could, through a more educated public, face positive or even neutral public reactions to their conditions, the impact of their conditions would become less handicapping. If this can be achieved, the benefits would be immediate and major. These campaigns seem to assume that providing the public with accurate information will motivate people to become more understanding and/or empathetic, and ultimately behave in less discriminatory ways toward those who have the undesirable conditions. Historically, attitudes have been shown to improve for some stigmatizing labels of the past, e.g., being labeled as “insane” or “a witch” (Porter, 2001). Herek, Capitanio & Widaman (2002) found that the overt stigma for AIDS declined slightly in the 1990s even though stigma still remained strong. Similarly, although public understanding of mental illness improved from the 1950s to the 1990s, stigma was not “defused” (US Surgeon General, 2004). For some physical handicaps, reduction of stigma over time is more encouraging. Individuals in wheelchairs are less stigmatized than they were in the past (Harris, L., et al., 1991; Nabors, 2002; Smart, 2001). Nevertheless, numerous examples are reported where public education campaigns apparently have not changed attitudes to the extent expected (Gelder, 2001; Harris, Walters, & Waschull, 1991; Lee, 2002).

Campaigns utilize a variety of forums and strategies though which to change attitudes. Some are electronic or print media, famous people with disabilities, school curricula, and professional or self-help group advocacy. To effectively evaluate the success of forums and educational strategies, valid and reliable measures of public attitudes must be developed

Needs and Challenges in Measuring Attitudes Related to Stigma Cross-Culturally

In the case of stuttering, no standard measures have been widely used to examine public opinions and attitudes or to establish baseline data against which to measure changes in attitudes, beliefs, and reactions. There are at least two important implications for this lack of baseline data. First, it has been impossible to determine which communities, regions, and societies are more or less knowledgeable or negative in their views about stuttering and therefore, where education efforts might be targeted. Second, without baseline data it is difficult to determine if public education initiatives have achieved their desired effects.

Survey Methods: Stuttering

Most measures of public attitudes or stigma ask people about various aspects of disorders or their own reactions to them. In studies of stuttering, a wide variety of data collection methods have been used: paper-and-pencil questionnaires (Blood, Blood, Tellis, & Gabel, 2003; Gabel, Blood, Tellis, & Althouse, 2004; Hulit & Wertz, 1994; Klein & Hood, 2004), semantic differential scales (Doody, Kalinowsky, Armson & Stuart, 1993), questions to store clerks who had just spoken with a severe stutterer (McDonald & Frick, 1954), face-to-face interviews with people on the street (Van Borsel, Verniers, & Bouvry, 1999), telephone interviews (Craig Hancock, Tran, & Craig, 2001; Ham, 1990), open-ended written statements (Ruscello, Lass, Schmitt, & Pannbacker, 1994), and extended tape-recorded interviews (Corcoran & Stewart, 1998; St. Louis, 2001), among others. A similar range of methods has been used with other conditions, and other innovative methods have been reported as well. For example, health professionals have directly rated the amount of stigma associated with health conditions (Bramlett, Bothe, & Franic, 2003; Ustun, et al., 1999).

Instrument Criteria and Considerations

After reviewing established international opinion surveys and contemporary survey research principles (Babbie, 1990, 2004; Dillman, 1978; Dillman, 2000; Quine, 1985; World Values Study Group, 1990-93) the task force established a number of instrument criteria. One primary requirement is that the survey can be translated to different languages and, thereby, be usable in a wide range of cultural settings. A second requirement is that subsequent translations must meet acceptable standards of reliability and validity. In early discussions, the task force recognized the value of providing respondents with exemplars, such as hearing an audio or video clip of a person stuttering or of providing a standard definition of what is to be judged. This seemed important since stigma is usually associated with the

Therefore, a written questionnaire format was chosen that neither defines nor provides exemplars of the conditions, but allows respondents to indicate that they do not know about the disorder. Despite some threats to the validity of results, e.g., respondents not realizing that stuttering might include speech with silent blocking, the task force believed this to be the best choice considering reliability, expense, availability of telephones or computers, adaptability, and the need for translation to other languages. A hard-copy survey could meet four major challenges to elicit objective nation-specific data in ways that would be (a) interpretable from probability and non-probability samples (described later), (b) obtainable for reliability and validity measures, (c) familiar to other cultures and countries, and (d) readable and amenable to the translation circle from American English to other languages and to back-translations in English, thereby permitting tracking and evaluation of semantic variability in languages.

The text that follows reports development and initial field-testing of the first American English prototype of the survey instrument and on other practical and methodological issues. These were considered important first steps in developing an empirically-based survey instrument that (a) applies theory and methods from population research in epidemiology and other health and social sciences with regard to issues such as respondent selection and sampling (Lubker, 1997; Lubker & Tomblin, 1998), (b) conforms to accepted ethical and methodological standards of survey research, (c) conforms to accepted standards of reliability and validity, (d) allows translation into different languages for multi-national use, and (e) allows quick and efficient analysis by investigators.

Purpose

This study was undertaken to field test the first prototype of the

Are stuttering ratings affected by the order of occurrence of stuttering versus other attributes in the questionnaire?

Can systematic results be achieved through convenience sampling when independent research partners distribute questionnaires?

Is a quasi-continuous rating scale efficient for respondents and data tabulators?

Does convenience sampling yield representative demographic characteristics?

Are respondents' comments suggestive of a user-friendly survey instrument?

Method

Questionnaire

Content and Format

The

Because a prohibitively large number of potential items would be required if each prototype questionnaire contained all nine attribute-specific

Quasi-Continuous Rating Scale

The first

Respondents' ratings were converted to numeric data by student and paid data entry assistants. In a procedure described by Breitweiser and Lubker (1991), assistants placed a transparent ruler, on which were printed numeric values, from 0 to 100, over each item on the survey scales and noted the locations of respondents' vertical marks. They then wrote the ruler's number, from 0 to 100, closest to the respondent's mark in the margin to the right of the scale. Respondents' marks at the middle marker (i.e., “neutral”) were recorded and tallied as 50. After ratings were converted to numeric values, assistants entered values for each section of each questionnaire into Microsoft Excel worksheets for analysis.

Other, non-scaled items also appeared on the survey. For example, in the last set of prompts in the

Length of the Prototype Instrument

The printed length of the

Counterbalancing and Randomization Scheme

The first purpose of this field study was to determine the extent to which the order of stuttering ratings was affected by ratings for other attributes. Stuttering ratings occurred both as items along with

Accordingly, three levels of randomization were used. First, a systematic counterbalancing and item randomization scheme controlled for effects of

Within each of these three

Second, content of packets with different survey versions was systematically varied before packets were given to partners/distributors for distribution. Research assistants prepared and collated packets in which successive questionnaires followed the various counterbalanced orders according to the samples shown in the bottom of Figure 2. In each packet of 14 or more questionnaires, adjacent POSHA-Es systematically varied in terms of

Distribution of Questionnaires

Nonprobability Respondent Sampling Scheme

Respondent sampling procedures are emphasized in survey research and in the health sciences, particularly in epidemiology (Greenberg, Daniels, Flanders, Eley, & Boring, 1993; Gordis, 1996). Simple random sampling to select survey respondents seems to be the

Distribution Procedures

A central distributor gave questionnaire packets to other distributors who in turn gave individual questionnaires to potential respondents who either completed them or, in a few cases, recruited others to complete the survey. This is described by Dillman (1978) as the “person in charge” method. Specifically, the first author (KSL) gave packets of questionnaires to seven university “partners.” Four students were enrolled in an honors class, and two were engaged in independent research experiences. The seventh student was visiting from another institution. The students assumed the roles of distributing and collecting that international partners are expected subsequently to perform. The student partners distributed the questionnaires to family members, friends, acquaintances, and small groups. The only inclusion criteria were that survey recipients must be able to read English, be at least 18 years of age to comply with approved human subject protection policies, and be willing to consider filling out the

Results

As noted, the purposes of this field study were to field test the first prototype of a survey instrument to measure public attitudes toward stuttering with special attention to (a) potential order effects inherent in the questionnaire; (b) a partner-recruitment questionnaire distribution pattern; (c) problems in scoring, tallying, and accuracy of responses on a quasi-continuous scale; (d) readability; and (e) comments and suggestions from respondents.

Respondent Characteristics

As noted, the intent of the nonprobability sampling procedure was not to achieve a representative (i.e., probability) sample but to explore the feasibility of methods that can be used in many cultures and in developing countries. Nevertheless, information about the extent to which the respondent sampling procedure produced a respondent sample deviating from census data could be used to inform analysis and utility of such sampling in interpretation and comparisons with public opinion data. Table 2 was prepared to compare the respondents in this field study with data from the US Census (US Census Bureau, 2000). It is clear that the collection procedure produced a sample of respondents, 67% (111/165) of whom were from West Virginia (WV), that was quite different from census characteristics of (a) the host county, (b) other counties representing at least 3% of the respondents, or (c) the state. US Census data indicate that only 15% of WV adults over 25 years report a bachelor's degree or higher. The table shows that the percent of ?25-year-old respondents whose demographic information reported at least 16 years of education (assumed to be generally equivalent to a bachelor's degree) in the sample groups is generally higher than would be expected in a probability sample of adults from counties and the state. The only notable exception occurred for the host county (Monongalia)—where 27% of the respondents resided—in which US Census data indicated that 32% of adults over 25 possessed bachelor's degrees or higher. More important, Table 2 reveals that county and state populations have an approximately equal sex distribution, different from the unbalanced distribution of the respondent sample, which contained about 2 ½ times more females than males.

POSHA-E Order Effects

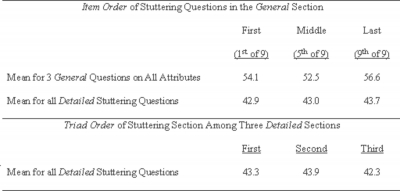

Figure 5

These means reflect the combined ratings of all nine attributes across all 27 scale items from the first three prompts in the

It should be noted that a correction for multiple t tests, such as the Bonferroni correction (Maxwell & Satake, 1997) to minimize the probability for making a Type I error was not applied in these and in subsequent parallel comparisons. In these cases

Finally, and perhaps of greater interest, the overall mean ratings for

Figure 6

These results were highly significant when stuttering appeared as the first or middle attribute in the

Accuracy and Care in Responding

The average number of scale responses was 245 per questionnaire calculated from 14 randomly selected questionnaires that were counted individually. Of the total responses, fewer than 1% of the ratings could be regarded as suspect for the above reasons [287 errors / (245 items x 165 respondents) x 100% = 0.7%].

Respondents occasionally rated two items on the same scale line. In these instances, no responses were tallied for either item. Nine questionnaires (5.5%) contained at least one of these kinds of errors, with a total of 10 errors that represented only 0.02% of all scale ratings.

Based on the very small percentages of presumed errors, we concluded that respondents generally marked the quasi-continuous scale with sufficient care that the tallied responses could be considered valid measures of their opinions. Nevertheless, the number of questionnaires that contained at least some problems (nearly one-third) ultimately led the task force to consider a different response mode.

Readability

Several authorities on survey research have addressed the importance of readability, wording and question clarity in questionnaires (e.g., Babbie, 1990; Dillman, 1978, 2000; Fowler, 1995). A general principle among experts is “keep it simple.” However, Dillman (1978; 2000) also discussed the pitfalls of over-simplification in wording and item construction.

Components of the

The readability rating of the

Comments from Respondents

Thirty of the 165 respondents (18.2%) wrote comments about the

Summary

This field study generated valuable data for proceeding with the IPATHA initiative. Whereas surveys are often generated and tested with limited attention to methodological issues presumed not to affect results, the task force believed that the

Not surprisingly, the model of convenience sampling employing partner distributors did not achieve a respondent sample that was representative of the geographic population of adults; however, it did achieve a sample that reflected a considerable range of ages, occupations, religious affiliations, marital status, and other demographic variables. Finally, although most respondents filled out the questionnaire without comment, those who did comment were likely to point out problems of length, confusion, and difficulty.

Discussion

Overview

A field study was conducted to field-test the first experimental prototypes for the

Respondents

The nonprobability sampling scheme was carried out by seven different student partners, each distributing questionnaires to acquaintances, friends, family members, and others known by these individuals. The most important caution of these data collection procedures is that they produced a respondent sample biased by selection. The selection resulted from cultural, social, and educational characteristics of the selecting partner. A major consequence is that results from analyses of this respondent sample are not generalizable to public opinion and attitudes. This sample helps to inform the need for control strategies when data are analyzed. The return rates from 35% to 89% per partner suggests that this strategy could effectively be replicated with other national and international partners.

Questionnaire

Length

“There is a widespread view that long questionnaires…should be avoided” (de Vaus, 2002, p. 112). A review of the evidence, however, indicates that there is little research to support this commonsense assumption. Seventy-five percent response rates for mail questionnaires with as many as 24 pages are reported (Dillman, 1978). The

Order Effects

The distributed questionnaires in this field study contained uniform representations of three triad orders for detailed stuttering section and various permutations of the two detailed sections of the other eight anchors. The exception is that an approximate equal representation was not achieved for the three item orders of stuttering in the general section.

The field study indicated quite clearly that the order of presentation achieved by counterbalancing strategies had little effect on respondents' ratings on any measures or any sections. Results suggested that in subsequent field tests it is appropriate to utilize only one

Readability

The principles of readability have important implications for those who seek to improve knowledge, to change attitudes and to measure these changes. The questionnaire readability rankings seem not to be a problem for this sample of respondents who, as a group, are more highly educated than the population in the surrounding community. The levels of readability may pose significant problems for less educated respondent samples. The inconsistency between tenth grade level of the instructions, mean fifth grade level of the survey items, and readability inconsistency among items will be addressed in subsequent field tests. An essential consideration is whether instructions at a high school level are useful among less well-educated populations whose knowledge and opinions about stuttering and other characteristics may be underrepresented in results of this and other surveys. Their knowledge, beliefs, and susceptibility to change agents may be significantly different from those in more highly educated strata.

Rating and Tallying Accuracy

The quasi-continuous scale occasioned a small but appreciable number and variety of inaccurately marked responses. Thus, methodological concerns for response attrition and for unusable responses were raised. While respondents' recording errors had inconsequential effects on the results, it became increasingly evident that the quasi-continuous rating scale too often produced invalid, unusable responses. The data reduction procedure was cumbersome and time-consuming for the quasi-continuous scale, requiring 20 – 40 minutes for each questionnaire. For this reason, if for no other, an interval scale will be considered for the final POSHA instrument.

A sample of re-measured and retallied questionnaires in the study indicated that inconsistencies between data entry assistants and a validator were negligible. Furthermore, comparisons of responses to the quasi-continuous scale with the 9-point EAI scale found similar attitude ratings.

Future Research

Other field tests of

When additional field test data are available, item analyses will determine which items are most discriminating and which are redundant or not useful. The next activity is to develop a shortened, revised version of the

With acquired sampling information, we are alerted to specific sampling questions for the larger international project. As noted above and shown in Table 2, respondents did not represent the area population. Educated persons and white females were over-represented. Future field studies will be designed to investigate these distributions in other non-representative samples and compare these distributions with results of probability sampling methods in some settings.

Considering that many international samples will not be generated by probability sampling methods, the possibilities for control at analysis rather in design, weighting procedures for sample representation, and other sampling manipulations can be explored for data generated in other cultures and communities.

This initial field study represents progress in moving toward the long-range goal stated in the introduction, that is to explore specific methodological issues in the ongoing process of developing an instrument to measure public attitudes toward stuttering. In this process, we are amassing a vast amount of data from on-going field studies that can be analyzed to identify country- and culture-specific attitudes and biases toward stuttering, other conditions, and differences. Inefficiency with the quasi-continuous scale and the use of nonprobability samples notwithstanding, this and other field studies under way allow us to carry out analyses of comparative data on attitudes toward stuttering within the context of other human attributes. Such contextual information can provide preliminary baseline data to inform strategies to modify negative attitudes. Accordingly, we intend to generate baselines indicating where attitudes are more or less positive and how attitudes are associated with one other.

The data from these ongoing and subsequent studies will allow analyses of demographic variables to determine differences in attitudes in controlled, stratified and appropriately weighted analyses of respondent populations' characteristics. Such knowledge about factors associated with people's attitudes is postulated as an essential foundation for those attempting to change attitudes.

Acknowledgements

This paper is dedicated to the late Charles C. Diggs, who was on the original task force. He would have been a coauthor of this paper were it not for his untimely death in 2006. We wish to acknowledge the valuable assistance of Jami Ebbert, Sharon Helman, James D. Schiffbauer, Carolyn I. Phillips, Andrea B. Sedlock, Lisa J. (Hriblan) Gibson, Rebecca M. Dayton, Amanda K. Cassidy, Rachel Fender, Amanda K. Efaw, Maren Greig, and Brenda Davis in collecting, scoring, tallying, and analyzing data.