Oral Pharmacological Augmentation Strategies for Adults with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Alternatives to Antipsychotics and Clomipramine

J R Scarff

Citation

J R Scarff. Oral Pharmacological Augmentation Strategies for Adults with Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder: Alternatives to Antipsychotics and Clomipramine. The Internet Journal of Psychiatry. 2014 Volume 3 Number 1.

Abstract

Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) afflicts millions of individuals and consists of distressing obsessions or compulsions. Many patients may require augmentation of first-line medications to achieve symptom reduction or remission. Antipsychotic agents and clomipramine have demonstrated efficacy for augmentation. There is increasing evidence to support augmentation with alternative medications that modulate serotonin, gamma-aminobutyric acid, glutamate, dopamine, or opiate receptors as well as second messenger systems and the immune system. These agents deserve further exploration in larger, longer studies.

Introduction

OCD is a heterogeneous disorder that afflicts approximately 2% of individuals in the United States and the world.1,2 It consists of obsessions, compulsions or a combination of both.3 Obsessions are recurrent and persistent thoughts, impulses, or images that are intrusive and inappropriate and cause anxiety or distress.3 Compulsions are repetitive behaviors or mental acts that the person performs in response to an obsession, or according to rules that must be applied rigidly.3 These behaviors or mental acts are aimed at preventing or reducing distress or preventing some dreaded event or situation.3

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) are recommended treatments.4 However, only 40%-60% of patients respond to an initial trial.5 This translates into millions of individuals displaying significant symptoms after receiving initial treatment. What options can we offer symptomatic patients who are receiving maximum doses of a serotonergic medication or who cannot tolerate higher doses?

According to the Practice Guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association, patients demonstrating a moderate response can be augmented with an antipsychotic agent; patients with little or no response may switch among or between classes of serotonergic medications or receive augmentation with an antipsychotic agent. 4 If patients continue to have no to moderate symptom reduction, clinicians can switch augmenting antipsychotics or augment with clomipramine.4 First (typical) and second-generation (atypical) antipsychotics and clomipramine have demonstrated efficacy as augmenting agents.5- 13 However, these strategies raise concerns: What options do clinicians have if medication-switching or augmenting with antipsychotics or clomipramine was not helpful? What do we do if the patient declines or does not tolerate augmentation with an antipsychotic or clomipramine? The Practice Guidelines offer alternative augmentation strategies including buspirone, pindolol, morphine sulfate, inositol, or glutamate modulators.4 This article reviews these and additional alternate strategies.

Methods

A search of the PubMed database was conducted to identify trials of augmenting agents for OCD. This search was limited to publications in English from January 1955-January 2014 of trials of oral medications available in the United States. It excluded trials of antipsychotics, clomipramine, non-oral therapies, case reports, monotherapies, and patients younger than 18 years of age. Unless noted otherwise, response is defined as partial (25%), moderate (30%), or full (35%), based on the percent decrease in the Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale (YBOCS).14

Serotonin (5-HT)

Serotonin dysregulation is implicated in the pathophysiology of OCD, and clinical improvement is correlated with decreased serotonin in platelets, decreased serotonin metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF), and increased serotonin in whole blood. Modulation of this system with SSRIs and SNRIs is first-line treatment, and attempts have been made to further modulate this system with buspirone, ondansetron, and granisetron. Buspirone is a post-synaptic 5-HT1A partial agonist evaluated in four trials (Table 1).15-18 The first study was an open-label trial where patients had received fluoxetine monotherapy of varying duration (7-48 weeks) prior to study entry, and they received supportive psychotherapy throughout the study. The second study was a double-blind crossover study, but the one patient who responded also showed improvement in depression. This contrasts with the third study, a double-blind placebo-controlled trial, where responding patients showed no improvement in depression. The fourth study was an open-label trial. Investigators questioned whether buspirone exerts efficacy by reducing obsessions or compulsions directly, or rather by alleviating comorbid generalized anxiety.

Ondansetron and granisetron antagonize the 5-HT3 receptor and reduce nausea. However, receptor antagonism also reduces anxiety-related behaviors by increasing GABA release; this in turn decreases mesolimbic dopamine release and right orbitofrontal cortex activity – two areas of hyperactivity implicated in OCD.19 These antagonists have been evaluated in 3 trials (Table 2).19-21 The first study was an open-label trial, and results are confounded by patients taking various concurrent medications. The second study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, but results are interpreted with caution since fluoxetine was started concurrently with ondansetron, and benzodiazepines (BZD) were allowed for sleep. Authors in the third study chose granisetron because it has fewer drug-drug interactions, easily crosses the blood-brain barrier, and has a good tolerability profile. While this study was also double-blind and placebo-controlled, results are confounded since fluvoxamine was titrated after 4 weeks.

Pindolol treats hypertension by antagonizing noradrenergic receptors, but it also antagonizes presynaptic 5-HT1A receptors, activity of which increases anxiety. Antagonism also promotes increased serotonin release. Four studies evaluated pindolol as an augmenting agent (Table 3).22-25 The first study was an open-label trial with overall negative results; lack of efficacy was attributed to pindolol’s short half-life. The second study was an open-label design, and patients spent only 4 weeks receiving augmentation with solely pindolol; responding patients noted improvement only after tryptophan addition. The third study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial which assessed whether pindolol shortened response time to SSRI administration. Although response criteria were stricter (response defined as >35% reduction in YBOCS score), pindolol did not shorten response time. The fourth study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in which responders noted a decrease in YBOCS scores starting in the fourth week of treatment.

In short, results regarding buspirone augmentation are mixed, though it may be beneficial for patients with comorbid generalized anxiety disorder. Adverse effects with buspirone were nausea, sedation, and headache. The 5-HT3 antagonists appear to be moderately helpful; most common adverse effects were headache, anorexia, and sedation. Pindolol appears to have overall negative findings, but may be helpful with addition of tryptophan. No adverse effects were associated with pindolol.

Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA)

Gamma-Aminobutyric Acid (GABA) is an inhibitory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. It is possible that increased inhibition can decrease obsessions or compulsions. Gabapentin (GPN) was evaluated in one open-label trial,26 and all patients reported improvement in anxiety, sleep, mood, obsessions, and compulsions within 2 weeks (Table 4). However, no rating scales were used, there was no standard gabapentin dose, and many patients had comorbid anxiety and depressive symptoms which improved. The most common side effect was transient gastrointestinal upset.

Glutamate

Glutamate is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the central nervous system. Glutamate dysregulation has been noted in neuroimaging of patients with OCD.27,28 In addition, symptom improvement has been correlated with decreased glutamate in the caudate, while elevated glutamate levels are noted in CSF of patients with OCD.27 Several studies have explored the efficacy of glutamate modulators (Table 5). These modulators include topiramate, pregabalin, lamotrigine, riluzole, memantine, and minocycline.

Topiramate inhibits glutamate neurotransmission and enhances GABA activity. Four studies evaluated topiramate.29-32 The first study was an open-label design which defined response as a 30% reduction on YBOCS. Responding patients noted that compulsions improved before obsessions. The second study was a retrospective open-label case series which used the Clinical Global Impression scale (CGI) rather than the YBOCS to assess outcomes. Responders still reported an average CGI score of 4.6, indicating significant residual symptoms. In the third study, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial, the treatment group experienced significant reduction in compulsions only. Investigators questioned whether obsessions take longer to improve, or whether patients with predominant obsessions need psychotherapy for symptom improvement. The fourth study was a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled design which noted efficacy for the treatment group. Adverse effects included weight loss, sedation, and word-finding difficulties.

Pregabalin modulates release of glutamate and monoamines and was evaluated in 2 studies.33,34 The first study was a case series which defined response as a 30% reduction in YBOCS scores. In addition to decreased obsessions and compulsions, responding patients noted improvement in anxiety and depression, and patients receiving benzodiazepines were able to cease use by the end of the study. The second study was an open-label trial which defined response as a 35% reduction in YBOCS scores. Similarly to the other study, patients stopped benzodiazepine use within 4 weeks. Adverse effects included vertigo and fatigue.

Lamotrigine inhibits glutamate release by inhibiting sodium and potassium channels and has been evaluated in 2 studies.35,36 The first study was a small case series, but the fourth study was a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. The second study also evaluated neurocognitive function and noted no change from lamotrigine augmentation. Adverse effects included sedation, fatigue, headache, and rash.

Riluzole reduces glutamate release, potentiates glutamate reuptake, and blocks GABA reuptake and was evaluated in 2 studies.37,38 The first was an open-label trial which defined response as a 35% or greater improvement in YBOCS scores. Responding patients also noted significant improvement in depression and anxiety. The second study was a case series which defined response as >35% reduction in YBOCS scores. Similar to the other study, responding patients also noted improvement in depression and anxiety. However, results may be confounded by supportive or cognitive-behavior therapy provided at follow-up visits. Adverse effects included headache, nausea, fatigue, and insignificant increases in hepatic enzymes.

Memantine is an N-Methyl-D-Aspartate (NMDA) receptor antagonist and was evaluated in 3 trials.39-41The first was an open-label trial in which responding patients noted improvement after four weeks. The second study was an open-label trial, but results may be confounded since patients received 2-4 hours of cognitive-behavior therapy daily. The third trial was a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group trial in which the memantine group showed symptom reduction and appeared to have accelerated response to fluvoxamine. However, fluvoxamine was initiated in the first week and then titrated in the fourth week. Some patients receiving memantine reported nausea, headache, constipation, drowsiness, or anxiety. The antibiotic minocycline also enhances glial glutamate transport and was evaluated in an open-label trial which defined response as 30% reduction in YBOCS scores.42 Although only 2 patients responded, they suffered from comorbid hoarding disorder and early-onset OCD. No adverse effects were reported.

Dopamine

Agonism of the D1 receptor is associated with increased attention and working memory.43 This could lead to fewer obsessional thoughts as patients gain ability and energy to shift attention away from them. However, dextroamphetamine did not separate from placebo (300 mg caffeine) in a double-blind trial43 (Table 6). Improvement in depression was reported only in the caffeine group, and 25% of treatment-group patients required dose decreases due to tachycardia, hypertension, or nausea. Other adverse effects included insomnia, dry mouth, and low appetite.

Opioids

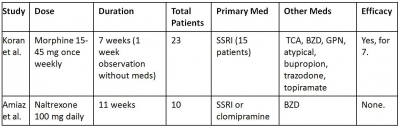

Implicated in the pathophysiology of OCD, the caudate nuclei contain many µ-opiate receptors. Stimulating these receptors inhibits GABA receptors, which may disinhibit serotonergic neurons in the dorsal raphe nucleus and periaqueductal gray matter, thus increasing serotonergic tone. Opiate receptor agonism may also decrease glutamate release in the prefrontal cortex. Opioid augmentation has been evaluated in two double-blind, placebo-controlled studies (Table 7).44,45 In the first, patients received once-weekly morphine, lorazepam, or placebo in 2-week blocks. The morphine and lorazepam groups noted symptom improvement, but morphine was not more efficacious than lorazepam. Morphine appeared to have greater effect when it was the first drug administered. All responding patients received at least one medication; that is, none of the six patients who received morphine monotherapy responded. Morphine was associated with sedation, nausea, vertigo, and fatigue. In addition, one responder (who had denied substance abuse at study entry) admitted to a history of opiate abuse after study completion and relapsed due to re-emerging OCD symptoms. The second study, a double-blind, crossover design using naltrexone found no difference between treatment and placebo groups. The authors speculated that there could be a “therapeutic window” for naltrexone efficacy. Patients receiving naltrexone did not report specific physiological adverse effects, but they did note increased depression and anxiety.

Second Messenger System

Inositol is a precursor in the phosphatidyl-inositol cycle, which is the second messenger system for several neurotransmitters, including serotonin. Some experts have theorized that inositol could benefit patients by increasing serotonin. Inositol was evaluated in 2 clinical trials (Table 8).46,47 The first study was a double-blind crossover design, and failure of the treatment group was attributed to investigators’ “high hopes” for inositol and patients’ desire for efficacy from a natural compound. The second study was an open-label trial which used a significantly lower inositol dose. In both studies, patients receiving inositol experienced gastrointestinal distress, but none withdrew from the study.

Immune system

Inflammation is noted in several psychiatric illnesses, and cytokines may precipitate or exacerbate symptoms. Cyclooxygenase inhibitors decrease inflammation, and anti-inflammatory agents can reduce cytokine concentration and thereby reduce OCD symptoms. Celecoxib was evaluated in one double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (Table 9).48 However, fluoxetine was started simultaneously and oxazepam was provided as needed for insomnia. Adverse effects included decreased appetite and gastrointestinal distress. Symptom improvement could be attributed to decreased prostaglandin production, increased serotonergic and adrenergic neurotransmission, or a combination of both.48

Limitations and Considerations

There are several limitations to this review. It was limited to articles in English and excluded trials of patients younger than age 18, monotherapies for OCD, or case reports. It is difficult to compare and generalized study findings, even of the same augmenting agent, due to variation in study design, criteria for response, low power, concurrent medications or psychotherapy, comorbid psychiatric conditions, and patient demographics. Is it possible that some serotonergic agents are more amenable to augmentation than others? Does the number of previous medication trials predict efficacy of augmentation? Does augmentation improve symptoms of comorbid psychiatric conditions rather than OCD itself? Can outcomes of an augmentation trial be influenced by concurrent psychotherapy? Many trials were of a relatively short duration: It is plausible that an augmenting agent thought to be ineffective could become effective with a longer trial, or conversely, that an effective augmenting agent can lose efficacy over time. What are the potential long-term adverse effects of these agents? Furthermore, these agents vary in cost and some may not be affordable for many patients. A sobering fact is that many studies sought reduction in YBOCS scores, which equates to response, not remission. This means that many patients, even responding patients, still displayed clinically significant and disabling symptoms. Finally, many trials excluded geriatric patients, despite the fact that OCD is a chronic condition known to afflict individuals into late life.

Conclusions

OCD is a chronic condition that affects many people. Many patients may respond partially to serotonergic monotherapy and may achieve symptom reduction or remission only after augmentation. Apart from antipsychotics and clomipramine, other medications have been evaluated, but assessing efficacy may be limited due to concurrent medications and study design and duration. More research is needed with these agents to answer questions of efficacy and to reduce symptom severity in patients of all ages with OCD.