Teachers’ Perceptions Of Effective Interprofessional Clinical Skills Facilitation For Pre-Professional Students: A Qualitative Study

R Cant, K Hood, J Baulch, A Gilbee, M Leech

Keywords

education, healthcare students, interprofessional education, interprofessional teaching, medical, pre-professional education, qualitative research, undergraduate

Citation

R Cant, K Hood, J Baulch, A Gilbee, M Leech. Teachers’ Perceptions Of Effective Interprofessional Clinical Skills Facilitation For Pre-Professional Students: A Qualitative Study. The Internet Journal of Medical Education. 2013 Volume 3 Number 1.

Abstract

Background

The introduction of interprofessional learning may help to produce healthcare graduates who are skilled in working collaboratively and in teams. Few studies have examined how teachers might conduct such interactive education.

Objective

This paper examines interprofessional teachers’ perceptions of key features of interprofessional teaching. During 2011-2012, pre-registration medical, nursing and allied health students (N=756) participated in interdisciplinary clinical workshops and seminars around ten clinical skills topics.

Methods

Twelve of 20 clinical teachers attended focus groups or interviews to provide feedback about key issues related to conduct of IPL.

Results

Four emergent themes were: ‘Skills for IPL facilitation’; ‘Strategies for success’, ‘Teachers’ learnings’, and ‘Teachers’ perceptions of student learning outcomes’. Teachers reported positive experiences in facilitating interprofessional clinical skills sessions, and perceived benefits for students. Successful interprofessional teachers were thought to apply specific facilitation skills to engage mixed student groups in meaningful exchanges of knowledge, clinical skill or technical aspects of patient care. Effective teaching was seen as dependent upon clinical skills topics being related to each discipline’s curriculum and being suited to shared learning.

Conclusion

Teachers valued IPL and would like to see it incorporated the curriculum. Findings included perception of improvements in students’ skills and greater understanding of other profession’s roles. Although teachers suggested a need for further specialty teacher education, they were keen to utilize IPL in the future. We present details of how teachers managed the facilitation of interprofessional learning.

Introduction

The higher education sector is being asked to produce healthcare graduates who are both a specialist in their own field and a collaborative team member in the workplace. This follows recognition that interprofessional teamwork may enhance patient care and reduce the risk of mortality and morbidity.1,2 Teamworking has been linked to improvements in patient safety in hospitals, in long-term care centres and in primary care settings.1,3 In the medical field, there is recognition that professional practice will, in the future, be based on teams and an international study recommended team-based learning be incorporated during training.4 Ideally, improving the teamwork skills of a health workforce would commence with learning during pre-registration studies.5 This would be achieved by students undertaking shared, or interprofessional learning (IPL); experiencing how to work together across professional boundaries in practice-based settings.6,7

In Australia, interprofessional learning has become a core curriculum objective for medicine, nursing, midwifery and pharmacy health professional qualifications7-10 although not yet implemented.7 Other allied professions such as physiotherapy, occupational therapy and paramedicine are incorporating this training.11

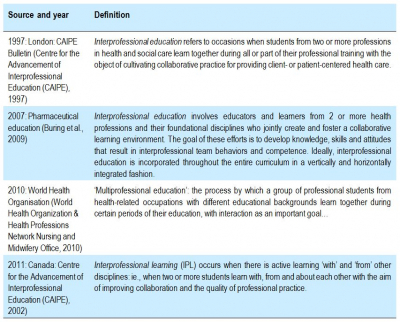

Interprofessional learning occurs when there is active learning ‘with’ and ‘from’ others: ie., when two or more professionals learn ‘with, from and about each other’ in order to improve collaboration and the quality of practice.12 (see Table 1) The literature around delivery of IPL has focused on development of implementation models13,14 or on student satisfaction in terms of their perceptions of their learning.7,15,16 In studies of ‘training wards’ there are reports of program evaluations17,18 and of positive student outcomes.19 What is missing, however, is detailed description of competencies that are required of teachers to effectively facilitate this education.

Pre-registration students have diverse scholastic backgrounds and face diverging learning requirements owing to curriculum requirements that advance at different rates. Students in various courses experience different socialization at universitiy20 and in the health workplace resulting in significant differences between attitudes towards learning interprofessionally.21,22 For example, students in medicine and physical therapy rated members of their own professions as more competent and autonomous, and more necessary to cooperate with in order to learn together compared with those in nursing and occupational therapy.21 These factors and our own research experience suggest that interprofessional teaching is a challenging, specialist skill that needs further exploration and explanation.

In a recent survey of interprofessional education (IPE) implementation in 41 countries Roger et al23 found that IPE was poorly developed and evaluated, with few IPE programs being taught by facilitators who had received any training. We consider that by having self-taught facilitators deliver IPE there is a risk to pedagogy in that students who may be situated in the same clinical education room revert to learning with their own group- intra-professionally. Therefore we report the views of a number of teacher-facilitators of IPE who have received IPE training, are experienced in the field and can offer information about its conduct.

The current report forms part of a longitudinal study conducted by researchers from Monash University and Southern Health (Victoria, Australia) that developed an interprofessional clinical learning program for pre-registration healthcare students during their clinical placements. From 2010-2012, multiple interprofessional clinical learning opportunities were offered to students from one university in nine pre-registration health care degree courses: Medicine, Nursing, Midwifery, Paramedicine, Nutrition/Dietetics, Physiotherapy, Pharmacy, Speech Pathology and Occupational Therapy. The settings were the acute care hospitals and related health services of a large health service in Melbourne. Over the period of their clinical placement, students were invited to attend scheduled interprofessional workshops, seminars, tutorials and simulation training sessions. The details of the teaching intervention and the clinical topics are given in Table 2.

Based on a scale of 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), session feedback from student surveys was very positive, ranging from 4 to 5 for all items. Over the ten clinical topics all student groups agreed or agreed strongly they were ‘satisfied with the quality of the activity’ (N=756; mean 97.7%, range 95.0-100%). There were differences in response by discipline, however, with medical students’ ratings often lower and showing more variation than other student groups. This led us to question what the impact and value of this type of learning was for students in various disciplines and also to question how shared learning would best be conducted by clinical teachers. It has been well established that IPL does not necessarily take place by situating students from various professional groups in the same room, and that student-to student-discussions were required to enact true interprofessional education.6,24 The research question to be answered was: What are the features of an interprofessional learning environment that could impact positively on students’ learning? We asked interprofessional teacher-facilitators to answer this question.

Methods

Sample and data collection

A descriptive qualitative study using focus group and face to face interview was chosen as the most suitable method to explore this topic. Focus group interview allows an in-depth exploration of issues underlying a subject of interest and provides better quality information than other types of survey.25 Over 20 different teachers who provided IPL during the study period were invited to participate in a focus group after a period during which they taught interprofessional groups. Teachers who were unable to attend a group interview were interviewed individually to obtain their feedback (some teachers were geographically dispersed as the teaching service was intentionally located wherever students were placed).

Three focus groups and four semi-structured interviews were conducted by two trained researchers (RC; KH), over 20 minutes to 65 minutes per occasion. A question schedule was used as a guide to initiate discussion. This asked about what constituted IPL and how interprofessional teaching was conducted; what learning opportunities were thought successful; whether there were any barriers to or enabling factors that assisted them in providing IPL; what resources were needed; whether they perceived any benefits to students from IPL and how they would improve interprofessional teaching. All conversations were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by an independent transcription service.

Institutional and university ethics approval was received for the study, and each participant provided their written consent.

Data analysis:

Thematic analysis was conducted in two stages. In the first stage, the first author (RC) read and re-read the narratives. Open coding was used to identify and then record nominal themes and additional related sub-themes in each narrative.26 Five main themes and 22 sub-themes were identified and all the narrative sections that described each theme were tabulated. In a second stage, the main themes were used as an organizing template to analyze and cluster the sets of data.26 This allowed an orderly matrix of themes to be developed that together could offer some answers to the research question.

Although one non-teacher researcher (RC) conducted the primary analysis, another two researchers (AG; JB) who were also facilitator-teachers compared the themes with the narratives and confirmed these relationships were meaningful. In the following section, the key themes are discussed.

RESULTS

Of 12 teacher-facilitator participants, eight attended one of three focus groups and four were interviewed face to face.

Participant characteristics

The teacher-facilitators were all experienced clinicians. Ten were females and two were males. Six participants were registered nurses, three were medical doctors and three were allied health professionals. All were experienced in the supervision of uni-professional students within their field of work. Prior to the interprofessional project, they were offered a purpose-designed educational program that introduced the concepts of interprofessional teaching and learning, and they attended any of a series of face to face workshops and received a manual about how to conduct IPL. Training was conducted by academics who were independent of the teacher group.

Two registered nurses and one medical officer were the only staff who held an academic postgraduate teaching qualification. They were senior and experienced clinical education staff and they did not undertake the direct care of patients at the time. The two nurses had prior experience of routinely teaching clinical skills to pre-professional medical students as a single discipline, and were therefore well qualified to comment on differences in teaching techniques. In addition to conducting some IPL sessions, the two clinical nurse educators were responsible for planning, scheduling and organising the IPL program.

All the teacher participants had recent experience of interprofessional teaching, having been involved in the interprofessional teaching program and the conduct of serial IPL sessions related to their specialty.

Qualitative findings

Analysis of the discussions yielded four main themes: ‘Skills for IPL facilitation’; ‘Strategies for success’, ‘Teachers’ learnings’, and ‘Teachers’ perceptions of student learning outcomes’. Each of these is discussed below, with selected quotations being given that were regarded as representative of the teachers’ views. The terms ‘teacher’ and ‘facilitator’ were used interchangeably as both the expressions were in use.

Skills for IPL facilitation

Teachers explained their perceptions of the hallmarks of effective interprofessional facilitation (listed in Table 3). They thought that successful interprofessional teachers applied specific facilitation skills to bring together students from more than one discipline to engage with each other in a meaningful exchange of knowledge, clinical skill or technical aspects of patient care.

“if you’re think you’re delivering IPE, it’s not simply delivering a topic to whoever is in the room of different disciplines. But there are set overt activities that encourage the learners to problem solve together or analyse something together to get their perspectives on an issue or content.” (FG4)

This suggests that teachers used both experiential learning and reflective learning strategies to assist students to interact to work through a clinical problem. Generally IPL took place between individuals; at least two students from two different disciplines (eg., one third year nursing student and one fourth year medical student) with the groups duplicated in the classroom.

“One of my learnings was that it wasn’t going to happen just by having everyone sitting in a room together. But I actually needed to be a lot more active.” (Interview 1)

Medical doctors sometimes felt out of their depth.

“We’re not used to interprofessional [supervision], that is, we work together but we’re not used to being in there sharing, you know, [asking] “What you are doing there?” …this is very different for us.” (FG 2)

Teachers’ strategies included being directive by introducing students to each other, pairing them in work teams, facilitating inter-student discussion and generally making sure that there was verbal interaction between the groups. For example:

“Once in the classroom …it comes down to how you structure the activities but you have to deliberately pair them or group them because even though you might have them all in the classroom they’ll sort of gravitate towards their own discipline…” (FG4)

Several teachers allowed time at the start of a session for an introductory chat between students before they were expected to work together.

“I found that it was really important to have people actually discuss where they were from and how that topic related to them right at the start and then to keep checking in with that …” (interview 1)

Furthermore there was a perceived need to encourage students to communicate openly with each other even though they were often senior year students

“My general observation was that the students did need... most of them needed quite a bit of encouragement to speak, they weren’t as forthcoming and... so I had to really think about how to create that, …to give people a bit more confidence in speaking up.” (interview 1)

One reason for a lack of confidence understood by teachers was the differing levels of experience in the student group:

“For the medical students, …they’ve had a good solid 12 months, even in their third year- of interviewing, examining, reporting. They’re very comfortable doing peer presentations, big group presentations.

2nd teacher: Yeah.

Whereas nurses struggle a little bit. And look, that’s just … because they just haven’t got the weeks in their curriculum to refine their skills.” (FG4)

Another strategy was to be directive about key parts of the topic.

“What I’ve learnt about medical students, teaching them, is they need very, very clear directions. They need to be explicitly told this is important/this is not important. “You need to listen to this person, you need to listen to that person … That’s mostly it.“ (interview 3)

Failing this alert, the particular skills or knowledge of another discipline such as nursing might be thought not to be relevant and be disregarded.

“I think if that (the relevance of another’ discipline’s competence) is not very clearly demonstrated, it’s hard because medical students often just go “Well, I’m not really going to listen to that examiner because I don’t think it’s relevant …” (interview 3)

This was reflected in teachers’ comments about facilitating the interdisciplinary groups and the teacher’s hoped-for outcome.

“[the] most important thing is really that the different professions show respect and really value what the other interprofessional groups [contribute].” (interview 3)

Teachers thought it was necessary and also challenging to keep students engaged in the session and one way of achieving this was through developing a relationship with the student group.

“I could just sort of tell they - and it reflected in the feedback a bit - were not as engaged with [a new teacher]. I think the main reason is they didn’t know …what her role was, they didn’t really know quite how she was connected [with them]. So,…I think there’s a barrier that’s easily addressed.” (interview 3)

Teachers thought that interprofessional facilitation training or experience was essential to the program’s success when teaching medical students;

“I think it might be difficult to get any … pharmacist and put them into that environment …in the teaching team. So I think … they need to have skills in teaching and skills in working with doctors and medical students. So, that is a very big barrier … training up people in how to communicate with medical students.” (interview 3)

Some teachers felt that IPL facilitation experience helped their interprofessional facilitation skills, saying:

“I sort of found ways of increasing the ‘interprofessional-ness’ of it as I went…: Interprofessional learning wasn’t a model that I was trained in…” (interview 1)

Strategies for success in IPL programs

Students’ learning was thought to proceed best when there were equal numbers of students from the participating professions, and less well when there was a shortage in some groups owing to placement dates.

“we had exactly five medical students and five nursing students, so every single activity that we set up in that, whether it be looking at a picture of a wound to identify the aetiology or going out and interviewing and examining a patient, we could always make sure we had both disciplines paired. …in terms of implementing your teaching plan, it’s challenging if you’ve got uneven numbers.” (FG4)

The effectiveness of IPL was also seen as highly dependant on the chosen clinical skill topic, which should suit shared learning among disciplines.

“The best example of IPE is BLS- where you do have a shared requirement to assess the situation, come up with a bit of a [dilemma] , What are we going to do about this? What worked, what didn’t?” (FG4)

Further, effectiveness was seen to depend on topic choice being relevant to the learning objectives of each group and yet match to their stage of learning- groups may have different expectations of the depth of content required.

“In terms of the back pain component, that’s something that doctors would assess, or physiotherapists would assess, so I think there is value in sharing that together as well, and there are other areas. …even with nursing if you look at intensive care and so forth, like with cardio thoracic stuff. I mean, it’s mostly the same [thing].” (interview 1)

The chosen topic needed to be of value to students and this was reportedly emphasized to students, for otherwise they could be reluctant to pay attention because they were more focused on topics in their study course that incorporated summative assessments.

“[in IPL] I don’t think realistically they listen as much unless they’re told, to other professional groups. They don’t think it’s examinable, they don’t think it’s core, so that really has to be very explicit.”(interview 3)

Furthermore, there were a number of organisational issues to overcome that were related to a discipline’s curriculum load. These included achieving overall agreement between unit supervisors regarding their students spending time on interprofessional curriculum topics, when this would occur and how much time could be allocated.

“We’ve got to be sensitive to all of the other demands…. the skills we’ve done this year have been mainly procedural skills and most have been two hours, two and a half hours. That works better [than 3-4 hours]. Yeah, both morning and afternoon.” (FG4)

Teachers’ learnings

As one allied health professional teacher stated: “IPL - the more I’ve looked into it, and worked in it, the more excited I get about it.” (interview 1) Teachers reported positive teaching experiences and saw not only benefits for students but various learnings for themselves. For the participants, effective IPL sessions were perceived to be a multidisciplinary group facilitation process, in contrast with more traditional didactic methods or their uni-professional teaching. They found this type of teaching of interest and therefore more engaging, even though it was challenging. They viewed IPL as helping to break down professional silos in healthcare through close personal contact among the disciplines (both with students and with student supervisors) and the sharing of communications on a one-to–one basis. They were reflective about what teaching strategies and topics were well received or poorly received, and would apply this knowledge in future. Several teachers felt more confident to conduct groups interprofessionally and felt encouraged to seek out small groups for teaching in the future.

However, facilitators also recognized the logistical difficulties including arranging for students from different disciplines to be in the same place at the one time, given their timetables, and difficulties in gaining the release of students from disciplinary placement for IPL sessions.

Teachers’ perceptions of students’ learning outcomes

All teachers held positive views of IPL sessions and of the benefits to learning for students. They noted that students were able to practice their communication skills with someone from another discipline, a precursor of what would be required in future practice. Teachers suggested that students gained in knowledge and skills and developed a different perspective through seeing clinical tasks from the point of view of other disciplines and by sharing knowledge in a two-way communication.

“the benefits are they have a slightly different perspective, they gain knowledge and skills that they wouldn’t necessarily get…” (FG 3)

“maybe share a different perspective on things that could actually add a lot of value to their [patient] assessment.” (interview 2)

Others thought they learned about another’s role and had a better understanding of the skills of other professions and where the various professions’ tasks fitted into overall care.

“…quite a few of them said that they hadn’t realised what speech pathology did in terms of dysphagia…” (interview 1)

“I suppose it was a bit of a pushing out of role boundaries.” (interview 2)

Teachers thought there was value for students in working together because this would reduce artificial barriers between professional groups through becoming more familiar with representatives of other professions as individuals.

“[the] most important thing is really that the different professions show respect and really value what the other interprofessional groups contribute.” (FG3)

A nurse facilitator reported a conversation with a nursing student that summarised these learnings: The student was saying:

“…now I can go straight to that allied health person, I’d have more confidence to go and refer directly to that discipline because I know a bit about what that discipline does”. “And I think that came from working with an allied health student and a medical student, seeing the assessments they do and what kind of clinical issues you refer to which discipline.” (FG4)

DISCUSSION

Teacher-facilitators of IPL reported positive experiences in facilitating clinical skills sessions for interprofessional groups, and also perceived benefits for participating students. As described earlier in Table 2, the participating students were from a broad range of healthcare degree courses including medicine, nursing and allied health, although students were mainly medical and nursing students by virtue of their greater numbers and the selected clinical topics. The four main themes identified in this qualitative analysis of teachers’ views were ‘Skills for IPL facilitation’, ‘Strategies for success’, ‘Teacher learnings’ and ‘Perceptions of student learning outcomes’.

Information about teacher skills for facilitation of IPL is scarce 27 and specific teacher education may be an emerging field of expertise with demands beyond those of traditional teaching skills. In the current study, teacher-facilitators of IPL identified a need to be more proficient through applicable training for assuming the IPL role, where students bring multiple perspectives, skill levels and expectations – all of which needed to be melded and managed. Other studies concur, reporting that facilitation of IPL is complex and requires attention to the distinctive qualities that engender learning between students from different professions to modify reciprocal attitudes and behaviour, heighten awareness of self and others, and cultivate co-working.”27: ch1 The latter study27 identified six key competencies required of IPL facilitators, which were: Styles of facilitation; Planning sessions; Leading the group; Understanding how groups work; Group dynamics and Understanding individual behaviors. Alternatively, Reeves et al suggested that teachers need experience, practical skills and confidence to facilitate learning in interprofessional groups.28 According to Holland, facilitators require knowledge of IPL programs and of current interprofessional practice issues, as well as knowledge of the health and social care professions.29

These studies all prescribe some broad facilitator attributes rather than providing any detailed information about how facilitators should deliver teaching for small groups comprising mixed disciplines. Given that until now, health professional education has been conducted almost universally in uni-professional groups with nurses teaching nurses and doctors teaching medical students, it may be that clinical teachers have not developed skills to ‘meld and manage’ learning in interprofessional groups. This was borne out in the current study where medical doctors stated they were used to working together “but we’re not used to being in there, sharing, …this is very different for us.” The implication here was they were not used to working with disciplines other than medicine. Another interviewee commented about the need to prepare non-medicine interprofessional teachers by “training up people in how to communicate with medical students” indicating there were communication principles that needed to be known. Additional specialist teacher training was seen as desirable.

Internationally, a deficit in faculty training for conduct of IPL has been reported. A recent survey in 41 countries reported approximately one-third of 369 IPL teachers had received training.23 In addition, a review of IPL studies noted a particular lack of reporting of how faculty had gained their IPL skills, which may lead to questions about faculty skill levels and raises issues of a need for targeted training.30 They suggested that both IPL program development and its implementation require specific IPL competencies of staff.30 Our findings concur with those of others that suggest these programs require specialist teaching skills in order that programs are both well organized and well taught.27

There was a perception from teachers that IPL sessions were more optimal for learners when there were equal numbers of students from each discipline, yet teachers recognized the logistical difficulties of scheduling these numbers and struggled to conduct unequal discipline sessions. Difficulty maintaining equal numbers of learners from different disciplines was a consistent feature in our study and this finding concurs with reports from many studies which document various barriers to IPL.31,32 In a UK report,27 planning of the session received recognition as a key competency necessary for IPL facilitation. However, the ability of a given facilitator to predict the ratio and mix of learners and plan accordingly is often limited by time-tabling or barriers imposed by uni-professional requirements.

The teachers’ views about student learning outcomes concurred with the findings of other studies that reported students became better informed about other professions’ roles, teamworking, and the practice of collaboration between professions.33,34 Other studies noted these benefits to learning arose from shared learning, with authors such as Hean giving theoretical insights into how students learned interprofessionally, one from another in interactive exchanges of knowledge or skills.35 In developing a concept model of IPL, D'Amour & Oandasan suggested that learner outcomes include: knowledge of roles, communication skills and behaviours, reflection, and attitude change (mutual respect, open to trust; willingness to collaborate) as key learnings.36 In addition, in the current study the teachers noted that students’ confidence to communicate with other professional groups was an important factor, as has been flagged in the literature,37,38 suggesting that improvement in student interdisciplinary communication was a perceived outcome.

Perceptive nursing and allied health teacher facilitators felt they had not only gained experience in teaching interprofessionally but were also working for the broader good of their profession by enabling medical students (as future gatekeepers of medical treatment) to develop a better understanding of various professions’ roles. It has been well recognized that learning interprofessionally may facilitate the breaking down of professional silos32 where education is conducted uni-professionally and the professional groups have little interaction until they reach the workplace.31 Thus IPL, when implemented universally throughout student education, bodes well for their preparation towards working across professional boundaries.

Limitations of this study are recognised. This interview and focus group study utilized a purposive sample of clinical teachers and the results, as for any qualitative research, may not be transferable to other settings. Although every effort was made to systematically explore the narratives and to limit reporting bias, the nature of qualitative research means that the findings rely on the interpretation of researchers. The analysis may not have captured every issue relating to the teachers’ views. Teachers were from the professions of medicine, nursing and allied health. However, to canvas the views of each of these professions as a whole, a larger sample may have been required. Focus group and interview techniques offered the best opportunity to explore IPL teachers’ views regarding interprofessional clinical skills program facilitation. If IPL is to be expanded in the clinical placement setting, ongoing assessment of the perceptions of those involved in IPL facilitation will be required. Ideally, the current findings about teachers’ views might be strengthened by examining the agreement of the targeted student groups in further focus groups. Additionally, however, training in IPL delivery may need to be widely deployed in the clinical setting in recognition of the adaptability, dynamic interaction and high level facilitation which is often required of IPL facilitators.

Conclusion

Teacher-facilitators of IPL were very positive about use of the interprofessional teaching strategy. They regarded IPL as highly beneficial to students’ learning and would like to see it incorporated in the students’ curriculum in the future. They described true interprofessional education where there was interactive communication between disciplines and outlined features of the learning environment that were desirable. They perceived student learning outcomes that concurred with findings in prior studies, including improvements in skills and understanding of other profession’s roles. Although there was a suggestion that teachers needed further specific training to conduct this type of program, they were keen to utilize IPL in the future.

Acknowledgements

This study was conducted as part of the Increased Clinical Training Capacity Project at Southern Clinical School, Monash University, funded by a research grant from the Australian Government: Commonwealth Department of Health and Ageing. We wish to acknowledge the contribution of the various interprofessional teachers who were committed to the education of healthcare students.