Intrapersonal Processes and Post-Abortion Relationship Challenges: A Review and Consolidation of Relevant Literature

P Coleman, V Rue, M Spence

Keywords

abortion, interpersonal relations, sexual dysfunction

Citation

P Coleman, V Rue, M Spence. Intrapersonal Processes and Post-Abortion Relationship Challenges: A Review and Consolidation of Relevant Literature. The Internet Journal of Mental Health. 2006 Volume 4 Number 2.

Abstract

While the study of the psychological effects of abortion has received increased research attention over the past few decades, scholarship devoted to the topic of post-abortion partner relationship quality has been minimal. In this report, existing empirical work on abortion and intimate relationships is analyzed in the context of related research and theory. Evidence indicating possible adverse effects of abortion on the quality of relationships is initially reviewed. Then several logical intrapersonal mediators of associations between abortion experience and relationship outcomes are explored. Finally, adult attachment dynamics are described as a theoretically plausible moderator of associations between abortion experiences and relationship difficulties. Throughout the paper, the most salient gaps in the literature on abortion and relationship quality are highlighted with suggestions for future research provided.

Introduction

The identification of a pregnancy as “unintended” or “unwanted” is frequently based on relationship factors with such pregnancies more common when relationships are just beginning, nearing an end, or are otherwise tenuous (1,2). Decisions regarding resolution of unintended pregnancies are likewise relational, involving the couple's connection to each other as well as each partner's relationship to the developing embryo or fetus (3,4,5). If an unintended pregnancy is terminated, the induced abortion becomes a part of the couple's shared history with potential to impact their future.

Abortion, whether voluntary perinatal loss or involuntary perinatal loss, is very common in the United States. It is experienced by a significant percentage of women at least once by age 45 (6). Yet abortion is also well-established as a potentially significant stressor in the lives of those who experience it (7,8,9,10). Although relational aspects of abortion decision-making and adjustment are obvious, abortion is typically conceptualized individually rather than relationally in the scientific literature. A small number of studies have identified relationship issues as relevant to the choice to abort (1,11,12) and some studies have considered the role of partner support in women's abortion experiences (13,14). However, compared to the vast literature focusing on the individual experiences of women and their partners contemplating an abortion, undergoing the procedure, and adjusting afterwards, few studies have adopted a relationship perspective. As a result, the contemporary understanding of abortion is one that has been largely excised from the social and interpersonal realities of women's and men's lives.

The relationship context of abortion is complex with multiple components that should be analyzed individually and conjointly. The context is specifically comprised of intimate partners, family members including parents and children, friends, and all others whose behavior and attitudes potentially impact individual responses prior to the pregnancy, while contemplating an abortion, and in the months and years after an abortion. Relationship dynamics are bidirectional rendering it essential to likewise understand how abortion decision-making affects others in the individual's familial/social environment. This article addresses intimate partner relationships, a central aspect of the broadly construed relationship context. The focus is on relationship dynamics in response to voluntary perinatal loss or induced abortion; however where relevant there are periodic references to the literature on involuntary perinatal loss.

Given the limited scholarly attention devoted to the topic of post-abortion relationship quality, this article is an attempt to integrate all existing empirical work (identified with the PsycINFO, Sociology Abstracts, and Medline databases) with relevant research and theoretical material in order to formulate a clearer picture of how abortion may impact partner relationships. In these databases searches “induced abortion” was linked with the following terms: “partner conflict,” “relationship quality,” “sexual dysfunction,” “abuse,” or “intimacy.” This review offers concrete guidance for further study on the topic of abortion and intimate relationships. More specifically, answers to the following questions are explored: 1) What evidence suggests abortion is associated with subsequent intimate relationship difficulties? 2) What are the possible intrapersonal mechanisms mediating associations between abortion experience and relationship outcomes? 3) Does adult attachment style moderate post-abortion relationship quality? 4) Where are the most salient gaps in the literature on abortion and relationship quality and what are the most pressing research needs on the topic?

Induced abortion and the quality of intimate relationships

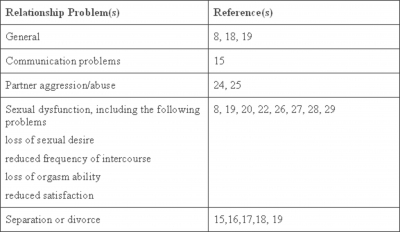

Many couples choose abortion to resolve an unintended pregnancy based on the belief that the decision will preserve the quality of the relationship if one or both partners feel psychologically or materially unprepared to have a child (1,11). Are these couples correct in anticipating that an abortion is likely to be in the best interest of their relationships? Although the research on this topic is limited, the available data reviewed below (and summarized briefly in Table 1) are beginning to suggest just the opposite for some couples, with abortion introducing significant challenges and stress into the partnership.

Conflict and communication difficulties

Partner conflict may logically arise during the abortion decision-making process if there are differences in opinion regarding how the pregnancy should be resolved and/or if relationship-based information, such as commitment, desire to ever have children, confidence in a partner's parenting abilities, life-style factors, and long-term intentions such as school or career plans are addressed. Post-abortion psychological effects on the part of one or both parties may conceivably add to earlier conflicts and/or new relationship problems could emerge following the procedure. For example, the abortion could lead to negative emotions including anger, guilt, grief, depression, and/or anxiety (reviewed in detail below), which can elevate the risk for ambivalent, withdrawn, antagonistic, or aggressive partner-directed behavior.

Partner communication problems following abortion exist (15), and there is an increased risk for separation or divorce following an abortion (15,16,17,18,19). In one study by Lauzon and colleagues (18), 12% of the women and 18% of the men indicated that an abortion performed up to 3 weeks earlier had adversely affected their relationship. Rue and colleagues (19) reported that 6.8% of Russian women and 26.7% of American women indicated relationship problems caused by an abortion experience; whereas relationship benefit was reported by very few Russian women (2.2%) and American women (0.9%). These authors provided hypotheses regarding the cross cultural difference in rates of negative consequences. They specifically suggested that Russian women may become more desensitized to the procedure due to the common practice of using abortion as birth control. Or alternatively, significant economic, social, and political stressors associated with Russian life may render Russian women more “stress experienced” than American women. Based on cultural norms, Russian women are conceivably more reluctant to disclose personal information as well.

Other studies suggest few post-abortion relationship changes (8,20,21,22). The contradictory findings in the literature may be due to variability in methodological rigor across the published research. The few studies that have examined abortion and relationship quality with results suggesting no meaningful impact of abortion generally relied on retrospective data and/or used only brief unstandardized measures of relationship quality (20,21,22). There is a prospective study (23) that followed couples from late pregnancy until 21 months postpartum and reported only a 5% separation rate. However, this is the exception as other prospective studies report much higher rates of separation [e.g., (16).

Minimal research attention focuses on abortion as a predictor of domestic violence. However, a few studies show an association between a history of abortion and increased risk for partner-perpetrated aggression during a subsequent pregnancy (24,25).

Sexual dysfunction

Research demonstrates that women with an abortion history are at an increased risk for sexual dysfunction (19,20,22,26,27,28). For example, in a recently published study, 6.2% of the Russian women and 24% of the American women reported sexual problems that they directly attributed to a prior abortion (19). In a Swiss longitudinal study of over 100 women, 31% reported a minimum of one sexual problem 6 months after an abortion (27). Sexual desire, frequency of sexual intercourse, orgasm ability, and sexual satisfaction are among the female sexuality variables explored in the literature. In a recent review, Bradshaw and Slade (8) concluded that 10-20% of women experience abortion-related sexual problems in the early weeks and months after an abortion, while 5-20% of women report sexual difficulties a year later. Male responses to a partner's abortion have not been extensively studied; however, post-abortion sexual problems in the first three weeks post-abortion were indicated by 18% of men, who were significantly affected by a partner's abortion (18). More research on abortion and male sexuality, particularly the long-term impact is needed.

The available studies generally indicate that sexual problems after an abortion are higher than in the general population. For example, in a study by Mercer et al. (29), persistent sexual problems lasting at least 6 months in the preceding year were identified in 6.2% of men and 15.6% of women. Sexual problems in women and men may be due to depression which is a common mental health problem following abortion (8,9) or the reasons may be more complex. Very few of the existing studies on abortion-related sexual difficulties probe deeply into why the problems arise. Results of one study revealed that decreased sexual desire was associated with not feeling worthy of one's partner (22). Further, in studies examining sexual problems associated with involuntary perinatal loss and/or loss of a child in which sexual problems have been identified in over 60% of couples, reasons for disinterest in sexual activity have been described and include depression, fatigue, numbness, preoccupation, and discomfort with sexual activity (30). The discomfort was based on sexual activity serving as a reminder of the previous conception, fear of pregnancy and another possible loss, and viewing sexual pleasure as incompatible with mourning. In this literature, gender differences have been documented wherein bereaved men are more inclined to find sexual intimacy comforting and to experience significantly less loss of interest as compared to women (30,31).

Although studies designed to examine the issues behind post-abortion declines in sexual activity are generally missing from the literature, variables that researchers might logically explore in future studies include any of the following: 1) perceptions of a partner as insensitive or insufficiently supportive, 2) negative abortion related emotions on the part of one or both individuals, 3) altered self-perceptions which may result in feelings of estrangement from one's partner, 4) anger due to relationship-based information (e.g., commitment, long-term plans, etc.) derived through the abortion decision-making process, and/or 5) history of unresolved grief and trauma in one or both partners.

Methodological issues

Correlations between abortion history and relationship quality could be explained by confounding additional variables associated with the choice to abort and with relationship problems. Few previous investigations of associations between abortion and partner relationship quality have incorporated controls for potentially confounding additional variables. Among the more obvious possible confounding variables are relationship problems or partner violence prior to the abortion, age, sexual risk taking behaviors, a childhood or adult history of physical or sexual abuse, history of prior voluntary (abortion, adoption) or involuntary pregnancy losses (miscarriage, stillbirth), and other sources of stress including poverty that could be associated with the abortion decision as well as relationship problems afterwards. Future research will ideally be prospective in nature, measuring relationship quality before and after the abortion, while incorporating controls for a wide range of additional potentially confounding variables.

In the published literature, with the possible exception of sexuality variables and communication, the dependent variables have been broadly defined assessments of relationship quality, conveying very little information regarding the aspects of relationship functioning that may be more likely to be impacted by an abortion experience. Prospective assessments addressing specific aspects of relationship quality such as conflict, affection, reciprocity, equity, interdependence, trust, commitment, and respect administered before and after an abortion would provide valuable data pertaining to relationship vulnerabilities as well as insight into mechanisms through which an abortion is likely to impair relationship quality. Ideally the pre- and post-abortion assessments would incorporate both open-ended questions designed to examine the respondents' thoughts and feelings regarding how the abortion may have affected various aspects of relationship functioning and standardized relational and psychological testing. Without a substantially developed literature on particular relationship outcomes associated with abortion, discussion of how abortion affects relationships remains limited and lacks the specificity necessary to realistically guide future investigations. What is known is that there is considerable correlational evidence associating abortion with general indicators of relationship problems. There is also documentation of abortion-related intrapersonal responses. Therefore, one logical place to turn in efforts to understand why abortion is often linked with relationship difficulties is to examine how intrapersonal variables associated with abortion may predispose a couple to distinct relationship challenges. This approach of addressing individual responses with an emphasis on intrapersonal processes most likely to influence interpersonal dynamics should provide a foundation for understanding how relationships are influenced by this common medical procedure. Without a well-developed understanding of personal responses to abortion, attempts to elucidate relationship issues are thwarted and could lead into fruitless directions.

Abortion, mediating intrapersonal processes, and relationship dynamics

Abortion-related beliefs

No one would deny that an induced abortion is the voluntary termination of a pregnancy, but considerable ambiguity surrounds interpretations of the meaning of this reproductive outcome. Abortion may be viewed by some people as little more than the removal or destruction of a cluster of cells, which carry the potential to develop into a human being. Others might consider abortion, particularly medical termination, as the process of initiating menstruation, attending very little if at all to the status of the embryo. For still others, abortion is viewed as the termination of an immature human life. Each conceptualization undoubtedly fosters distinct notions regarding normative responses to abortion. For example, if abortion is primarily viewed as a simple medical procedure designed to revert the woman's body back to its pre-pregnancy state, one would expect the choice to abort to be met with predominantly positive feelings, such as relief and satisfaction and few, if any, negative psychological effects once the physical discomfort has abated. On the other hand, if abortion is viewed as the deliberate taking of a human life, one would anticipate profound feelings of guilt, remorse, and bereavement among others.

Abortion is often experienced as both a relief as well as a psychosocial stressor (31). In a Swedish study, two-thirds of the respondents expressed both positive and negative emotions in conjunction with an abortion, with the remaining one third reporting only negative feelings (32).

A woman's personal understanding of abortion is likely to impact her post-abortion adjustment. For example, in a large scale study by Conklin and O'Connor (33), women who believed the fetus was human and aborted were found to have more negative affect and significantly lower self-esteem and life satisfaction than women who had not aborted a pregnancy. Even weak beliefs in the humanity of the fetus resulted in associations between abortion and compromised well-being. Women who had an abortion but did not consider the fetus human scored similarly to those without a history of abortion relative to the three post-abortion adjustment measures. The authors noted that the results held up even after statistically controlling for contextual variables and they emphasized the significance of the findings based on how difficult it is to identify moderator effects in field research.

The idea of the fetus possessing at least some degree of personhood and moral objection to abortion seem to be commonly held beliefs. For example, research on women who had first trimester miscarriages revealed that 75% felt they had lost more than a pregnancy (34). Further, 25% of women facing an abortion decision considered the fetus to be human and regarded abortion as the taking of life (35). Allanson and Astbury (11) report that 25% of women seeking an abortion agreed with the statement “abortion is against my beliefs.” A number of other studies show that many women have abortions despite moral opposition to the procedure (11,35,36). In a recent study, 50.7 % of American women and 50.5% of Russian women who had an abortion felt abortion was morally wrong (19). Further, the results of a study by Lauzon et al. (18) revealed that the presence of a moral dilemma was identified as the greatest contributor to men's anxiety prior to a partner's abortion. Specifically, over a third of the men who reported being anxious about a partner's pending abortion (56% of those sampled) identified moral issues as the source of their anxiety. This indicates that for a significant number of women who abort and their partners, the decision is not an easy one and it is likely to have been resorted to in response to personal and/or situational pressures.

Each partner brings his or her personal perspective regarding the meaning of the abortion into the experience of an unintended pregnancy and its resolution. However, no quantitative studies have specifically examined each partner's beliefs about abortion as predictors of post-abortion relationship quality. The probability of discrepant views initiating conflict would seem to be quite high, particularly if one individual views abortion as the taking of a human life and the other views it as a simple medical intervention absent from any moral dimension. There are studies suggesting that women who feel pressured into an abortion by a partner have more post-abortion mental health problems (31), as do men whose partners have opted to abort against their will (36,37); however relationship factors were not examined as dependent variables in the studies conducted to date. With opinions regarding abortion varying greatly in our society and personal beliefs likely to affect the post-abortion psychological functioning of the individual, any effort to understand post-abortion relationship issues should begin by examining the history and strength of each partner's convictions regarding abortion.

Post-abortion guilt, anger, and self-reproach

Like mainstream society, professionals within the medical community and researchers alike continue to adopt disparate views of abortion, resulting in very conflicting messages regarding what constitutes normal post-abortion psychological adjustment. Such conflict is perhaps inevitable given the complexity of issues surrounding an abortion. Nevertheless, a lack of consensus may have slowed progress toward understanding the real-life experiences of women and their partners. Efforts to support men and women in resolving any psychological pain or relationship difficulties resulting from an abortion are likely to have been compromised as well. In an interesting admission pertaining to her efforts to assist a client working through an abortion, psychotherapist Kluger-Bell (39) states “What kept coming up in session after session was her guilt and regret over the abortion she had had six years before. Probably because of my own commitment to the legal right to abortion, I considered first-trimester abortion a fairly straightforward medical procedure with few if any long-lasting effects….I failed to recognize that in her present circumstances the abortion felt like a huge, irrevocable mistake.” (p.7) According to psychiatrist Philip Sarrel (40): “Abortion is frequently a negative turning point in a relationship leaving scars which can undermine the future of the couple either together or as individuals.” (p. 244)

Research shows that women's reasons for choosing abortion are overwhelmingly tied to their life situation as opposed to abstract, moral, or religious principles (41). Many women who are ethically opposed to abortion can make the decision to abort despite their personal views about abortion. This incongruence between women's beliefs and behavior is likely to engender guilt feelings, which are very common among women who have aborted. Available evidence specifically indicates that between 29% and 75% of women acknowledge feelings of abortion-related guilt (10,21,32). The results of a major national poll by the

Feelings of guilt may take on an existential dimension that becomes more pronounced with time, leading to preoccupation with the ramifications of the abortion. For example, women who feel as though they really should have carried to term may find the guilt causing them to obsess on what the child's life would have been like. For those who experience abortion as traumatic and are guilt-ridden, there may be continual self-punishment and an inability and/or unwillingness to be free of the attendant guilt. In an analysis of qualitative data, many women who had experienced an abortion in the distant past felt as though they had been on an emotional roller coaster for decades and found themselves frequently thinking about their abortions and the children they never delivered (44). Similarly, in another study (45), 73% of college women who had an abortion and 64% of college men whose partner had a past abortion reported having thought about what the child would have been like.

Guilt is an often associated feature of posttraumatic stress disorder, and although related, shame is a distinctive affective state that can further debilitate an individual and/or couple following an abortion (46). In the context of an elective abortion, guilt implies the act of having done something wrong and feeling the need to make amends. In contrast, shame tends to be more consuming wherein the entire self is negatively evaluated, resulting in feelings of worthlessness, powerlessness, and the need to hide or escape from others (46).

Many human behaviors that lead to feelings of guilt can be compensated for by apologizing to the offended party and/or by engaging in corrective behaviors; however, the finality of an abortion precludes engagement in such restorative behaviors to absolve one from guilt. Pregnancy termination is irreversible and if women are unable to come to terms with an abortion that evokes considerable guilt, the negative feelings may lead to more generalized feelings of self-reproach and/or they may cause the individual to engage in negative behaviors targeted towards one's partner. As psychotherapist Kluger-Bell (39) has noted “many women carry around unresolved feelings of guilt and shame which can tend to get expressed in self-punishing thoughts and behavior.” For example, a woman who is consumed by abortion-related guilt may begin to feel as though she does not deserve to be happy or to be the recipient of a partner's love. As a result, she may consciously or unconsciously engage in antagonistic behaviors that lead to relationship problems.

Nonvoluntary forms of perinatal loss are sometimes associated with intense, uncontrollable anger which becomes so unacceptable to the individual that it is turned inward and transformed into guilt and self-reproach (47,48). As noted by Hebert (48), women's efforts to understand the loss and reduce feelings of guilt may lead to preoccupation, intense introspection, and feelings of alienation, which result in the partner pulling away or feeling shut out. Anger after abortion has only received scant attention, but a small-scale clinical study of 30 women distressed by an abortion showed that 92% experienced intense anger, rage, and/or hostility (49). A few other studies have identified anger as one of various negative post-abortion emotions (43). In one study (46), abortion-related anger was reported by 13% as they faced the abortion and by 14% one year later. If a woman has a negative abortion experience, anger may be directed inward or outward. Externally projected anger could be targeted toward professionals involved in the abortion or significant individuals, such as a partner who is perceived as not having provided sufficient emotional support prior to, during, or after the procedure. Anger may also be logically directed at a partner because he encouraged or pushed for an unwelcome abortion. In addition to precipitating anger, guilt may cause psychological problems. Guilt has a well-established history of an association with mental illness, particularly depression (50,51).

Many women undoubtedly get beyond feelings of guilt, anger, and self-reproach through social and spiritual means and find ways to effectively forgive themselves (52). Kluger-Bell (39) notes that “Finding a place to remember and talk about one's abortion experience in support groups, in psychotherapy, or among friends – and demonstrating one's caring through rituals or ceremonies, which honor the aborted beings, can help in the process of reconciling one's view of oneself as a good person with the fact of having terminated a pregnancy.” (p. 76) Women often report that the feelings of abortion-related guilt prompted a religious conversion or a deepening of a religious commitment in order to experience forgiveness and peace (43,53). For example, a woman who had been particularly distressed by an abortion four months prior stated “a week ago I asked the child and God to forgive me and now I have started to talk to my partner …and this past week I have felt much better” (p. 2566) (43). More research is needed to examine guilt and self-reproach as mediators of relations between an abortion and relationship problems and to more systematically explore how personal efforts to resolve guilt may ameliorate any personal or relationship problems that develop after an abortion.

Abortion as a form of perinatal loss and associated grief

Abortion may initiate feelings of loss, as in nonvoluntary pregnancy terminations. In this section, research pertaining to nonvoluntary perinatal loss is examined, similarities and differences between nonvoluntary and voluntary perinatal loss are explored, and associations between post-abortion bereavement and relationship issues are discussed.

Grief involves a wide range of emotional and cognitive responses to a death (30) and it frequently draws the individual toward the missing person in response to awareness of the discrepancy between the way life is and the way one believes life should be (54). The nonlinear nature of bereavement results in many individuals revisiting various components of their grief numerous times as they work their way through the process (30). Grief has been conceptualized as “a voyage of healing and a rebuilding of meaning and representations of self” (55).

Nonvoluntary forms of perinatal loss are often experienced as a personal tragedy with substantial grief reactions. Approximately 25-50% of women who experience a nonvoluntary perinatal loss will suffer from clinically significant psychological distress (56,57,58,59). Fathers to be, like expectant mothers, are prone to experiencing significant levels of perinatal grief (60). Resolution of perinatal loss is believed to be particularly difficult, because memories of interacting with the child are lacking (61,62) and the significance of the loss may not be acknowledged by others in the individual's life (63). Due to inadequate opportunities to grieve and frequent insufficient social support, a distinct form of grief termed “shadow grief” is sometimes associated with perinatal loss. Rather than resolving more or less completely after a few years, this form of grief involves a life-long tendency to re-experience feelings of loss in response to cues, such as the anniversary of the loss (64). Because men are less likely to receive assistance and support in grieving a perinatal loss, they are believed to be more susceptible to shadow grief (65,66).

Compared to studies pertaining to nonvoluntary forms of perinatal loss, far fewer studies explore bereavement associated with voluntary loss. However, Williams (67,68) provided evidence of a common grief response among women who aborted and described abortion as a distinct form of perinatal loss. In one study (69), 77% of women who terminated a pregnancy due to fetal malformation reported acute grief. Further, another study (45) found that approximately 30% of college students who had an abortion or had a partner who had an abortion agreed or strongly agreed with the following statement: “I sometimes experience a sense of longing for the aborted fetus.” In another study (43), approximately 20% of women described severe emotional distress in conjunction with an abortion, with 43% reporting grief right before the abortion and 31% reporting feelings of grief one year post-abortion. Lastly, in another study (19), 33.6% of Russian women and 59.5% of American women who had an abortion responded affirmatively to the statement “I felt a part of me died.” Only one study measuring male bereavement was identified (70) and the results revealed that nearly 35% reported feelings of grief and/or emptiness four months after a partner's abortion.

One study (71) investigated the psychosocial sequelae of second trimester abortions for fetal anomalies two years post-event. This study revealed that most couples report a state of emotional turmoil after abortion. Twenty-percent of wives still complained of crying bouts, sadness, and irritability, while husbands reported increased listlessness, loss of concentration, and irritability one year post-event. The authors of this study concluded that a lack of synchrony in the grieving process, increased social isolation, and lack of communication resulted in marital disharmony in the aftermath of the abortion.

Bereavement is a complex and dynamic process marked by considerable individual variation (30); however healthy bereavement is generally accepted as resulting in the ability to resume other relationships and engage in new ones (63). Women who experience prolonged perinatal grief reactions indicative of unhealthy bereavement have difficulty thinking rationally about other aspects of their lives including relationships (72). Without sufficient opportunity to grieve a fetus lost through abortion, problems in relationships with partners may develop if one or both partners view the abortion as a loss.

No studies examine feelings of post-abortion grief as predictors of relationship problems occurring in the aftermath of abortion. A few studies indicate that nonvoluntary perinatal death is related to feelings of enhanced closeness between couples (73,74); whereas other studies indicate that up to 90% of bereaved parents separate or divorce within a year of a stillbirth or neonatal death (75)

If both partners do experience grief in association with an abortion, the nature and timing of their bereavement responses may differ considerably based on evidence of gender differences related to other forms of loss. For example, men tend to exert greater control over the expression of painful emotions, intellectualize grief, and cope alone; whereas females tend to be more expressive and employ process-oriented forms of coping (30,64,77). Men are also inclined to identify their primary role as supporter for their partners following perinatal loss (78). One study (66) found that although men displayed less immediate “active grief,” they were more prone to frequent feelings of despair long after a perinatal loss than women. In a long-term study of paternal responses to perinatal loss, grief intensity diminished over time, but remained mild to moderate 5 years later (79). Men are apparently more inclined to experience a chronic form of grief with perinatal loss, because they tend to be overlooked for support at the time of the loss (65).

There is evidence indicating that differences between a woman's and her partner's perinatal grieving can introduce conflict and stress in their relationship (64,80); however these studies have dealt exclusively with nonvoluntary perinatal loss. Discrepant grief responses are perhaps even more probable with abortion than with nonvoluntary forms of loss due to the higher probability of one partner not experiencing the abortion as a form of perinatal loss. With the nonvoluntary loss of a pregnancy that is wanted or at least accepted, one would expect a majority of expectant parents to experience some form of grief reaction. On the other hand, with abortion, only individuals who viewed the fetus as a person or developed some form of bond to the fetus prior to termination would be expected to experience grief. Under these circumstances, one individual may experience profound grief while his/her partner does not grieve at all and as one is eager to move on with his or her life, the other will have substantial grief concerns. When post-abortion responses are so dramatically different, the potential for conflict would seem to be quite high. Even in the situation wherein both individuals experience grief, the nature and duration of each person's grief could be highly variable based on the degree to which they would have preferred to continue the pregnancy in addition to their views of abortion and the humanity of the fetus. Future research on post-abortion relationships should explore the degree and nature of each individual's perinatal grief response while also examining each individual's perceptions and emotions regarding their partner's response to the abortion.

Mental health effects on men and women

Mental health problems triggered or exacerbated by an abortion experience may be involved with relationship problems occurring after an abortion. In the text that follows, the post-abortion mental health literature is reviewed initially and is then analyzed with reference to possible bases for mental health problems leading to relationship difficulties. The best evidence indicates that a minimum of 10-30% of women who undergo an abortion experience report pronounced and/or prolonged psychological difficulties attributable in large part to the abortion (7,8,10,81,82). Although the causal question has not been definitively resolved, the methodological rigor of studies pertaining to mental health correlates of abortion has increased considerably in recent years, thereby increasing confidence in the conclusion that for many women abortion does trigger psychological problems (83). More specifically, several published studies have now employed the following: 1) unintended pregnancy carried to term as the control group, 2) collection of data for several years beyond the abortion, 3) use of medical claims (with diagnostic codes assigned by trained professionals), which eliminates the problem of women concealing an abortion, 4) controls for prior psychological problems and a variety of potentially confounding personal and socio-demographic variables, and 5) use of large and often nationally representative samples (83,84,85,86,87,88,89).

The results of one particularly well designed study (89) indicate that while 42% of the women who had abortions reported major depression by age 25, 39% of women post-abortion suffered from anxiety disorders. In addition, 27% reported experiencing suicidal ideation, 7% had alcohol dependence, and 12% were abusing drugs. This was a longitudinal study which followed 1265 children born in Christchurch in 1977 and was strengthened by the use of comprehensive assessments of mental health using standardized diagnostic criteria, considerably lower estimated abortion concealment rates than in previously published studies, and the use of extensive controls. Variables that were statistically controlled in the primary analyses included maternal education, childhood sexual abuse, physical abuse, child neuroticism, self-esteem, grade point average, child smoking, history of depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation, living with parents, and living with a partner.

With 1.3 million abortions performed each year in the United States, a substantial number of women are likely to suffer from new mental health problems each year. Women who are negatively affected by an abortion may experience any of the following mental health problems: anxiety (37,86), depression (37,45,85,90,91,92), sleep disturbance (90,93,94), substance use/abuse (84,88,95,96,97), and/or increased risk of suicide (87,98). A number of the studies pertaining to mental health effects of abortion have focused on anxiety and a recent literature review indicates that 8-40% of women experience anxiety in the aftermath of abortion, with up to 30% of women suffering from clinical levels of anxiety and/or high levels of generalized stress at one month post-abortion (8).

Compared to the amount of research on women's post-abortion psychological responses, considerably less attention has been given to men's psychological adjustment to a partner's abortion. Nevertheless, the available data do indicate that male responses to a partner's abortion may include guilt, depression, anxiety, feelings of voicelessness/powerlessness, repressed emotions, and anger (9,19, 38,45,99,100). A recent review of the literature on male responses to abortion (9) found that many men defer the abortion decision to their female partners and tend to repress their own emotions in an attempt to support their partners. Long-term studies are therefore needed to accurately gauge effects of abortion on men.

Many of the studies that have identified negative effects of abortion regrettably assess outcome variables with very brief measures. However, in one well-designed study, Swedish researchers conducted a study of 854 women one year after an abortion using a lengthy semi-structured interview and found that rates of negative experiences were substantially higher than in earlier studies relying on brief assessments (101). Specifically, more than half of the women sampled reported emotional distress of some form (e.g., mild depression, remorse or guilt feelings, a tendency to cry without cause, or discomfort upon meeting children) and 16.1% reported serious emotional distress necessitating therapeutic intervention from a professional or being unable to work because of depression. This literature suggests that if one or both partners experience negative psychological effects of an abortion, the risk for relationship problems is likely to increase, particularly if those affected fail to seek outside help for pronounced difficulties.

There are numerous mechanisms through which post-abortion mental health problems may adversely affect relationships. Logical mediators include reduced emotional energy, withdrawn behavior, communication difficulties, feelings of self-doubt, limited personal control, decreased self-esteem, and/or blaming one's partner for suffering incurred. There is also a well-established link between mental health problems, particularly anxiety, and substance use and the development or exacerbation of a substance use problem would be expected to increase the probability of relationship difficulties (101,103). A final possibility is that individuals who suffer from post-abortion psychological disturbances may dismiss the abortion as the cause of their suffering based on common views of abortion as a benign medical procedure and look for reasons for their suffering within the partnership. Research is needed to examine how post-abortion psychological responses of various forms in one or both partners may adversely affect relationship quality.

Adult attachment style as a moderator of post-abortion relationship quality

In this section, research is reviewed related to different adult attachment styles, how attachment styles may factor into women's decisions to have an abortion, and the extent to which attachment styles may operate as a moderator of post-abortion relationship problems. According to attachment theory and supportive empirical data accrued over the past several decades, the quality of early relationships with caregivers lead to mental representations of oneself as worthy of love from others and to expectations regarding the availability of others to meet one's psychological needs (104,105,106,107,108). Because these schemas are believed to remain relatively stable throughout life and to impact the nature of relationships beyond the family of origin, particularly intimate relationships (109,110,111), they are a logical starting point in efforts to identify and describe possible moderators of associations between abortion and relationship quality.

The majority of adults interested in entering into long-term relationships identify responsive qualities associated with secure attachment as the most attractive characteristics in potential partners (112,113,114,115). Among the secure qualities identified are attentiveness, warmth, and sensitivity. Despite strong general endorsement of these characteristics, many individuals end up in relationships with individuals lacking these qualities. In fact, there is evidence indicating that individuals tend to find partners who confirm their existing attachment-beliefs, whether positive or negative (107,113,116). Secure individuals would be inclined to find partners with the above positive qualities, whereas insecure adults might be expected to pair with partners who are less responsive emotionally and who are less able to competently meet their affective needs. According to Attachment Theory, individuals who have childhood experiences of loss, rejection, or instability precipitating insecure attachment are at risk for involvement in adult maladaptive relationships where the distorted patterns of attachment behavior negatively impact subsequent loss experiences (117).

Adults with a secure attachment style compared to those with an insecure style report greater relationship satisfaction, have more enduring relationships, exhibit more trust, commitment, and interdependence, and their relationships are generally characterized by more active employment of compromise and other positive conflict resolution strategies (118,119,120,121,122). Perhaps because of these qualities, when compared to insecure adults, secure adults more readily seek support from their partners when distressed and provide more support in response to partner distress.

An unplanned pregnancy is typically experienced as a crisis (123,124,125) and the attachment system tends to be evoked under emotionally taxing circumstances (105). Adults are likely to feel safer and more secure when their partner is close, accessible, and responsive when confronting stressful circumstances (126). Men and women involved in unplanned pregnancies are confronted with their own emotional adjustment as well as the need to fulfill the role of providing comfort and support to their romantic partners. As the central attachment figure in an adult's life, intimate partners are likewise the logical recipients of any negative feelings such as regret, anger, or feelings of abandonment that may have resulted from an abortion.

The relationship ramifications of undergoing an abortion experience may differ dramatically in the context of a relationship between two securely attached adults compared to one in which one or both partners are insecure. Further, the extent to which individuals are able to effectively address their own pre- and post-abortion emotional needs, respond to a partner's needs for closeness, and avoid over-reacting to any negative partner emotional displays would logically vary greatly based on relationship duration and history, personal coping resources, situational factors, and other personality characteristics.

Planned pregnancy has been conceptualized for many years as a period during which women's attachment-related feelings stemming back to early childhood are intensified (127,128,129,130), with women who have had insecure relationships with their own mothers likely to experience considerable ambivalence during pregnancy. Exploration of attachment processes in the context of unplanned pregnancy has been minimal. However, the literature suggests that sexual acting out resulting in an unintended pregnancy may have some basis in unresolved conflicts surrounding separation from attachment figures (131,132). A recently conducted study (133) showed that college age women, who were anxiously attached, when compared to those with other attachment styles, were more willing to consent to unwanted sex based on frequently cited fears that their partners would lose interest if they refused to comply. Further, in a study of 635 woman attending an antenatal clinic (134), women with a history of more than one abortion, when compared to women with only one, were more likely to have had a childhood history of separation from their mothers for 12 months or more prior to age 16, in addition to reporting low levels of perceived maternal care during childhood. Insecure attachment may contribute to ambivalent feelings regarding parenting expressed as less reluctance to getting pregnant coupled with resistance to carrying to term (134). More recently in a study of 96 women seeking a first trimester abortion (135), women with insecure attachment styles, compared to those with secure attachment, were more likely to have reported one or more previous abortions.

Research devoted to examining how attachment styles might relate to women's abilities to cope with an abortion experience is scarce compared to studies devoted to understanding the relevance of attachment history to abortion decision-making. One study (136) indicated that women with mental representations indicative of the secure adult attachment style experienced significantly less self-reported post-abortion distress (depression, anxiety, hostility, and somatization) than women with mental representations suggestive of the insecure-fearful attachment style. However, no significant differences were observed between the securely attached and those with mental representations suggestive of two other insecure adult attachment styles (dismissing and preoccupied). A second study (137) showed that poor relationships with one's mother predicted high levels of post-abortion anger.

Future research exploring the relationship implications of abortion should take into consideration each partner's attachment style. The stress of an unintended pregnancy/abortion would seem likely to exacerbate insecurities if one or both parties do not possess a secure attachment style, possibly ushering in defensive, withdrawn, and/or destructive, relationship behaviors. In contrast, based on the existing theory and literature, it seems likely that secure attachment in both partners would predispose each individual to healthy adjustment prior to and following an abortion decision. Although this hypothesis has not been tested, research suggests that insecure adults tend to feel anger and hostility toward their partners and view their partners negatively after discussing conflict-based topics, whereas secure individuals often view their partner more positively after such a discussion (138,139). Further, compared to secure adults, insecure adults generally perceive their relationship as involving less love, commitment, and mutual respect (138,139).

Individuals with different forms of attachment handle emotions in distinct ways that are related to recovery from loss (140). Securely attached individuals who tend to have confidence in themselves and trust others are inclined to react emotionally to a loss, but would not feel overwhelmed by the grief. The self and other mental models that secure individuals possess are apparently protective during times of loss. An insecure-dismissing style is associated with a lack of trust in others and extreme independence. Insecure-dismissing individuals are therefore inclined to suppress and avoid attachment-related emotions resulting in very little overt expression of grief. On the other hand, an insecure-preoccupied orientation is marked by high emotionality, expressiveness, and a lack of trust in oneself. Attachment–related feelings are not coped with well and these highly dependent individuals would be inclined to become preoccupied with loss, leading to long-term rumination. Finally, insecure disorganized individuals lack trust in others and in themselves due to past traumatic relationships, and as a result they are at risk for highly troubled and incoherent grieving. Studies have documented associations between insecure attachment and unresolved mourning (141,142).

There are several additional reasons to expect attachment styles to have implications for post-abortion relationship issues. First, secure attachment is associated with being able to easily extend forgiveness to one's partner, since he/she is generally viewed positively with transgressions considered not characteristic (143). Forgiveness does not come as easily to insecurely attached individuals (143). Second, securely attached individuals tend to be more comfortable with self-disclosure and are inclined to view others as more responsive to their needs than insecurely attached individuals (144). Third, unlike individuals with a secure attachment, individuals with an insecure attachment characterized by negative views of self would be expected to fear rejection and may see the abortion as confirmation (145). Finally, attachment styles are predictors of mental health status. For example, in a clinical sample, insecure disorganized attachment was found to be related to high scores on measures of anxiety/panic, depression/medication, and alcohol consumption (54). If one or both partners suffer from a mental health problem, the probability of relationship problems is inclined to increase.

The empirical evidence described above indicates that women with an insecure attachment orientation are more likely than those with a secure attachment style to have an abortion, are at a greater risk for post-abortion negative reactions, and are more prone to interpersonal difficulties. Therefore an increased probability of relationship problems following an abortion seems highly likely if the woman and/or her partner have an insecure attachment style. More research is needed to examine how various combinations of attachment styles in the context of romantic relationships are associated with distinct post-abortion relationship trajectories.

Implications and conclusions

Surprisingly, little focused scholarly attention has addressed how abortion is likely to impact relationships in the months and years following the procedure. Limited progress may have been tied to concern that research findings indicative of increased risk of relationships difficulties could conceivably be used to restrict abortion access. Further, abortion has been largely framed as a “women's issue” in our society, so there may be hesitation among social scientists to broaden the scope of attention to include partners and relationships. Beyond the possible socio-political reasons for minimal research attention having been devoted to the topic, the sheer complexity of understanding relations between abortion history and relationship quality is daunting and may have stalled efforts in the area.

Adjustment to abortion varies dramatically. Even within the group who are adversely affected, the form and intensity of responses are highly variable (83). The range of effects on relationships can logically be expected to be even more diverse as the situation becomes complicated by two individuals' personal responses to the abortion and coping skills, the degree of congruence between their responses, and relationship strengths and weaknesses.

The prognosis for relationship problems post-abortion seems increasingly probable under certain conditions. Specifically, if one or both partners view abortion as the taking of a human life, would have preferred to avoid the abortion, developed an emotional connection to the fetus, experience negative emotions such as grief, guilt, and anger in association with the abortion, suffer from adverse mental health effects of the abortion, and/or possess an insecure attachment style, then the likelihood of relationship difficulties may increase. There are obviously many other variables that may play a role in the association between abortion and relationship quality, including various relationship factors (e.g., length, commitment, respect, trust/loyalty/dependability, and open communication), religiosity, whether or not the couple already has children together, history of previous perinatal losses, and personality characteristics to name a few.

Future research should consider all of the above variables as well as others in an effort to identify typical post-abortion relationship trajectories based on distinct socio-demographic, psychological, and relationship profiles. Table 2 provides an overview of the many personal, couple, and situational factors likely to have moderating or mediating effects on the quality of relationships after an abortion and should provide a framework for further work on this topic.

Figure 2

Future studies designed to illuminate adaptive and less adaptive strategies adopted by couples who experience traumatic grief responses in association with an abortion should provide insight into how couples cope with other forms of socially stigmatized traumatic events, which are difficult to share with people in one's social network. For example, when there is domestic abuse or extra-relationship sexual affairs, traumatic responses are likely to occur and may remain unresolved due to issues of shame, fear, and trust that may preclude reaching out to family and friends for support. When confronted by defining crisis events in relationships, successful intervention and healing requires increased communication, willingness to engage in communication about overwhelming emotions, the development of shared meaning, and the opportunity to discuss the experience with friends, family members, and/or support groups. Research on the topic of abortion and relationships carries potential to provide new understanding of how partnerships may break down and recover when the triggering issues involve highly sensitive, largely private, and emotionally laden experiences.

Theoretically, when couples face significant psychosocial stressors, such events can evoke the best or the worst in each other. If abortion is perceived by one or both partners as a traumatic event, it is likely to become a defining crisis in the relationship's history creating the possibility for increased intimacy and mutuality or relational decline resulting from attachment injury (146,147). Homeostatic maintenance of the relationship is unlikely.

At times of transition or of high emotional valence, (e.g., pregnancy loss in general or abortion in particular) attachment needs are salient. One of the most important relational requisites is that partners provide accessibility and responsiveness in time of stress or crisis. If attachment injury does occur, one partner is likely to feel betrayed due to the inaccessibility or unresponsiveness of the other partner. If feelings cannot be discussed and communicated in a primary relationship, trust and security are undermined and feelings of abandonment or betrayal can easily result (148).

Abortion of a wanted pregnancy (149) and an unwanted pregnancy (19,150) can precipitate posttraumatic stress disorder, as well as depression and anxiety. Having experienced an abortion as traumatic, it is axiomatic that symptoms of re-experience, hypervigilance and avoidance will be encountered (151). Along with the social stigmatization associated with abortion (152), these symptoms are both self-protective and self-defeating. They prevent emotional engagement yet precipitate the continuation of relational distress. Unlikely or unable to communicate with others to process their loss and grief, couples can experience an amelioration of the initial post-abortion distress, but never really recover and reconcile the experience intrapersonally or interpersonally (153). A “conspiracy of silence” between the partners places them at increased risk for isolation and alienation with the attachment injury, (i.e., abortion), presenting itself as a recurring theme in the ongoing relationship dynamics. Other adverse outcomes associated with abortion that are likely to significantly impact upon relationship functioning include alcohol or substance abuse, compulsivity in work or sex, eating disorders, premature replacement pregnancy, neglectful or abusive parenting, or becoming overly protective as a parent (154).

With intervention occurring early enough in cases wherein an abortion is construed to be a traumatic loss, there is hope for mitigation of pain. Support from one's partner, friends, family members, and health care professionals can help soothe reoccurring symptoms of grief and help to regulate negative affective states including posttraumatic symptoms of intrusion, re-experiencing and avoidance.

Abortion is generally not perceived by society or those who have obtained it as a “successful” experience. Rather, abortion is subject to considerable societal and individual ambivalence, including the stigma of “failure.” Because many couples are reluctant to share their abortion experience with others, it is incumbent on them to address possible attachment injury and grief responses either partner may have. Whether or not society changes its perception of abortion, women and men will need to continue relying upon their primary relationships to form the basis of a “recovery environment.” In addition, support groups for women and men who have experienced abortion are also available but limited, though some are growing rapidly (e.g., Rachel's Vineyard; http://www.rachelsvineyard.org).

Conducting a large-scale, nationally representative study is imperative. Such a study is needed to determine the factors associated with relationship difficulties and to gain an appreciation for the personal and relational strengths associated with positive post-abortion relationship adjustment. For example, do couples who adjust well display more sensitivity to their partner's unique support needs? Or perhaps those who adjust well to an abortion are more likely to seek support from others who have been through the experience? Do couples who adjust well tend to have a history of having worked through other challenging life situations? With information regarding how abortion may affect relationships and how other couples move forward with their lives after an abortion, couples can make an informed decision regarding pregnancy resolution and will be more prepared to deal with relationship issues that might arise if abortion is chosen.

Highly stressful events in a couple's life are complex and can be assessed simultaneously from both partners' viewpoints, yet to capture the depth of affect and relationship change, more novel approaches would seem warranted. One strategy (155) uses daily diaries in assessing couples experiencing a shared stressor. Such an approach offers potential for qualitative and quantitative measures of how abortion is likely to be experienced and also provides improved methods and opportunities for partner support both pre- and post-abortion. Examining the physical health effects of abortion on the well-being of a partner experiencing chronic stress associated with abortion may also prove beneficial, i.e., how gender, attachment, and relationship duration can predict the onset of cardiovascular reactivity to pregnancy and/or abortion related stress (156).

As research on this topic advances beyond the preliminary, exploratory stage, it will be important to design studies in which the investigator is able to decipher the extent to which abortion functions as a primary stressor, is a symptom of existing relationship problems, or perhaps functions as the event of sufficient magnitude to bring latent relationship issues to the foreground. To this end, future studies will ideally be prospective in nature with data collection extended over many years. This strategy will allow for measurement of personal and relationship variables prior to and after the abortion in order to more effectively ascertain relationship changes occurring in response to the abortion. A longitudinal data collection plan will further enable identification of various common patterns of adjustment defined by distinct phases of interpersonal challenges and/or periods of relief. For example, some couples may initially go back to life as usual only to find that months or years after the procedure relationship problems connected with an abortion surface. Others may initially experience the abortion as a crisis, devote concentrated attention to healing, and then find that they are able to effectively move on. Still other couples may arrive at the decision to abort together, offer needed emotional support to each other, and find that their relationship grows either stronger from the experience or weaker. Use of control groups of couples with similar socio-demographic characteristics who choose to carry an unintended pregnancy to term, who do not experience a pregnancy, and who adopt a child will also make establishing causal relations more feasible. Of these groups, the most vital one to include in subsequent investigations is unintended pregnancy delivered as any individual (e.g., guilt, depression, sleep difficulties etc.) or relationship (e.g., conflict, communication problems, loss of interest in sexual activity) correlates believed to be attributable to an abortion could in fact arise at least in part in response to the unintended pregnancy.

Finally, as efforts are made to understand the relationship context of abortion, research should also be increasingly devoted to analyzing the impact of other family members and friends on women's abortion decision-making and adjustment. In particular, the attitudes and behavior of parents of adolescents contemplating abortion should be analyzed more extensively. Levels of positive support provided and the degree of pressure exerted on their daughters to make particular reproductive decisions should be addressed. The quality of parent-child relationships before, during, and after an abortion decision might then be examined based on distinct parental responses approaches to providing assistance.

The cloak of silence surrounding abortion has left couples, some of whom may very well be at an increased risk for experiencing relationship difficulties, often struggling alone to understand and respond to relationship challenges in the aftermath of abortion. Essential first steps to change are acknowledging the potential of abortion to disrupt individuals' lives and committing to systematic exploration of the topic with the goal of establishing risk factors and profiles of couples prone to coping difficulties. With this critical knowledge, prevention is possible. Women and men who are partners of women seeking an abortion can be better advised of the relationship risks from this procedure beforehand and practical clinical protocols can be developed to minimize and ameliorate such possible adverse outcomes.

Correspondence to

Priscilla K. Coleman, Ph.D. Human Development and Family Studies Bowling Green State University Bowling Green, OH 43403 e-mail: pcolema@bgnet.bgsu.edu